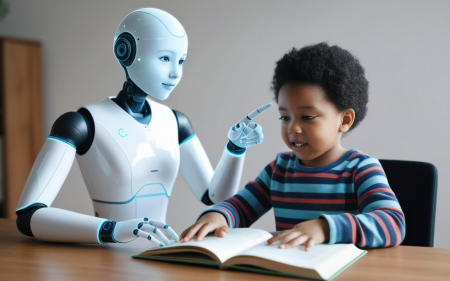

For millions of children, being dragged to a museum is a singularly painful experience, marked by time standing still rather than history coming to life – as it does in the film “Night at the Museum”, starring Ben Stiller.

But that all could change with the development of new “mixed reality” (MR) technology, which could inject new forms of interactive storytelling into our museums – introducing holographic tour guides and immersive digital displays in place of finger-smudged glass cabinets and faded information boards.

Unlike the total immersion of virtual reality (VR), or the computer screen required for augmented reality (AR), MR uses a head-mounted glass display, similar to the Google Glass spectacles, which enables the user to see their real-world surroundings while virtual features are overlayed on top, creating a sense of mixed perception.

To manage this feat, MR devices are equipped with sensors which are crucial for tracking the user’s movement. MR devices are also equipped with cameras, which detect cues from the environment to assist in the seamless superimposition of virtual features onto the physical world. All of this is achieved through the projection of 3D graphics onto the glass display – a process that creates a hologram.

As a result, visitors at future MR-enabled museums might find themselves hunting for lost pirate gold, evading booby-traps, or wading through crocodile-infested waters in search of informative clues. We tried to incorporate some of these thrilling features into our own experimental MR study in Cairo’s Egyptian Museum – which saw guests dodging warring charioteers, and dusting for ancient relics.

Our MR museum experiment in Cairo used Microsoft HoloLens hardware, and new software called “MuseumEye”. Ancient Egypt was a wonderful period of human history to bring back to life with the help of technology – though our visuals were more akin to “The Mummy” than “Night at the Museum”.

The mummy returns

In our MR museum experience, holograms of King Tutankhamun and his consort Queen Ankhesenamun lead visitors around the museum, discussing how they used to live and demonstrating how they would use some of the 120,000 tools and artefacts on display.

Making these ancient artefacts more accessible to visitors required us to 3D scan many of the exhibits, so that they could be rendered digitally as manipulable 3D objects. Scanned antiques were then fed into a programme called “Unity” which helped us map hand movements on to tasks – a pinch, for instance, was coded as a command to make an artefact smaller. The MR exhibition’s moving characters were modelled in the programmes “zBrush” and “Autodesk Maya”. As a result of this exhaustive coding work, visitors could “pull items off the shelf” and examine them in detail, using hand gestures sensed by the HoloLens.

Elsewhere, we animated reenactments of how the ancient Egyptian empire once went to war, with soldiers and chariots racing around exhibition rooms. We also offered guests the opportunity to become an archaeologist for the day, unlocking treasures hidden around the museum. By scoring points on discoveries made, we turned the museum learning process into a game – something that’s been shown to improve educational outcomes from museum visits.

Some 171 museum patrons evaluated the MuseumEye application, with over 80% finding the MR experience a significant improvement in interactivity, entertainment, and educational value. And there are other benefits: in a separate study, we found MR guides more cost effective than human tour guides, with the extra ability to provide real-time information on guest behaviour and section overcrowding.

Holographic history

A number of other museums have begun experimenting with MR. The National Holocaust Centre and Museum used the HoloLens to powerful effect in their “Witnessing the Kindertransport” exhibition. Over in New York, the Intrepid, Air & Sea Museum hosted an MR installation called “Defying Gravity: Women in Space”. And in Washington DC, the National Geographic Museum hosted “Becoming Jane” as a way to immerse visitors in the life and work of chimpanzee researcher Dr. Jane Goodall.

Beyond museums, MR is being put to use with the HoloDentist project, which helps trainee dental surgeons safely operate on virtual patients. The “.rooms” project, meanwhile, uses MR to assist interior designers, allowing people to walk around and change the furniture and features in their home.

Back to reality

As MR technology remains in its infancy, the devices currently available to developers are both limited and expensive – which is why the Egyptian Museum is not currently deploying the MR our team developed. One Microsoft HoloLens costs around US$3,500 (£2,570), and large museums may require as many as 300 headsets to run effective MR tours.

However, this technology does appear set for rapid growth. After Facebook’s Oculus Rift VR headsets failed to capture the public’s imagination, the company recently announced the release of their own brand of MR smart glasses, scheduled for later this year. In 2020, Nreal launched the U+ Real Glass MR headset in Korea as a cost-effective device for everyday use, with plans to expand sales into Japan and Europe over the coming years.

Our MuseumEye software has shown how MR technology can bring history to life, delivering benefits to both museums and their guests. With the release of new, reasonably-priced MR hardware, and the further development of hologram software, we expect museums to increase their engagement with MR in the coming years – making ‘Night at the Museum’ into an everyday reality.

- is Lecturer in Computer Games, Solent University

- is Research Fellow, Computing, Edinburgh Napier University

- This article first appeared on The Conversation