Imagine if Meta decided to make a car. It’s less outlandish than you might expect. The company has figured out ways to suck up all sorts of other user data so far. Driving data probably isn’t that low down on its list of priorities. But, for once, Meta isn’t in the spotlight here. Instead, everyone else is clamouring around the freshest trough of user-generated data.

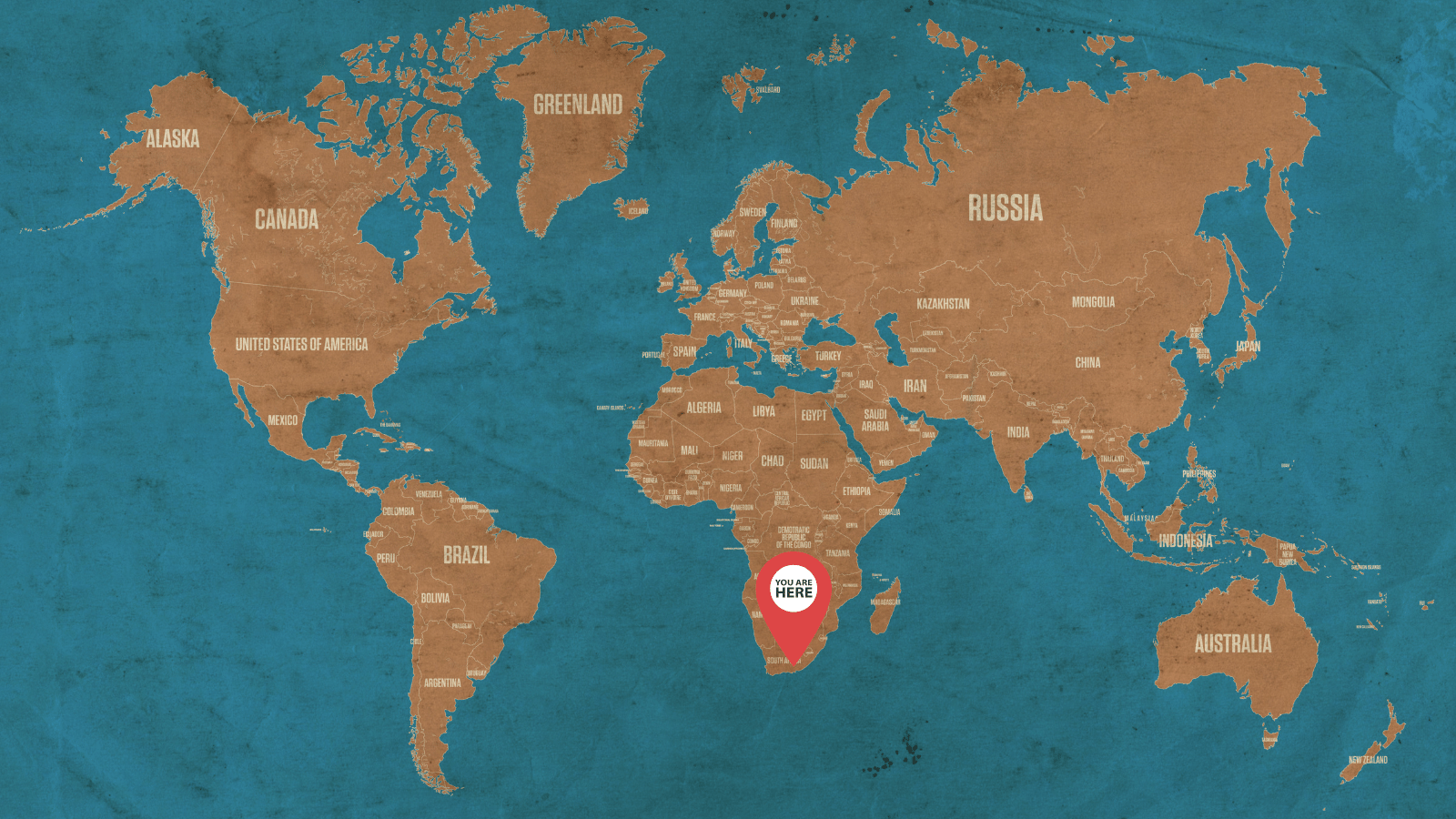

Driving data is the newest gold mine for… well, for anyone who has anything to do with the motor industry. Repair companies want it. Insurers want it. In South Africa, insurers are actively receiving it. Auto-makers want it, and they’re in a prime position to do the best data collection. This latter fact has led to the EU being called in to moderate ongoing fights between those collecting driving data and those who desperately want access to it.

Know your worth

Everything that you do generates data. That data is extremely valuable, but the large companies making money from it invest considerable resources in making sure you remain unaware of that fact. Or, at the very least, apathetic to it. Any time you post to Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram, you’re generating money for Meta. Any time you use Google to search for something, or Maps to get somewhere, you’re generating money for Alphabet.

The same is true for your fitness tracker, your smartphone, your laptop and TV, apps, and smart appliances like Meta’s Portal or Amazon’s Alexa. Even the intersections you drive through are using you to generate data that can be flipped for a profit. It shouldn’t be surprising that a target-rich environment (to borrow a military Americanism) like driving data is now on the menu. It’s equally unsurprising that you’ll rarely benefit from it in any tangible way.

Driving the future

Collection of driving data used to be difficult to achieve. But then we started fitting cars with LTE and, later, 5G. Suddenly, vehicles can report back to base. That gives everyone from Audi to Zhongtong (they make buses in China) the ability to monitor user behaviour inside vehicles. It’s why BMW has learned enough to be able to turn certain in-car features into a subscription service. That’s a very risky move unless you’re reasonably sure that most users only make limited use of certain functions at specific times. A cash discount now will almost always defeat a small credit card charge later. But it only works if driver behaviour is an open book to the manufacturer.

Collection of driving data used to be difficult to achieve. But then we started fitting cars with LTE and, later, 5G. Suddenly, vehicles can report back to base. That gives everyone from Audi to Zhongtong (they make buses in China) the ability to monitor user behaviour inside vehicles. It’s why BMW has learned enough to be able to turn certain in-car features into a subscription service. That’s a very risky move unless you’re reasonably sure that most users only make limited use of certain functions at specific times. A cash discount now will almost always defeat a small credit card charge later. But it only works if driver behaviour is an open book to the manufacturer.

Discovery Insure is a little more upfront about its data collection. Vitality Drive sticks an actual tracking device into customers’ cars. There’s a definite benefit to the driver, in that good driving is rewarded with cheaper premiums. And Discovery makes out on two fronts. First, a good driver is a less risky driver, so there are fewer insurance payouts to make. That’s the part you’re supposed to pay attention to. The bit you’re not looking at is where Discovery uses the metrics surrounding your drive. It drives the development of new products it knows will sell to its customer base.

Always watching

Google’s ubiquitous Maps software operates almost entirely on this principle. The company went to some effort to photograph streets around the world, but it’s the pervasive Android smartphone that drives the feature. Live traffic data? That’s generated by Android phones sitting still in traffic. A man called Simon Weckert documented exactly how this feature worked by using a small cart full of Android phones in 2020.

Google’s ubiquitous Maps software operates almost entirely on this principle. The company went to some effort to photograph streets around the world, but it’s the pervasive Android smartphone that drives the feature. Live traffic data? That’s generated by Android phones sitting still in traffic. A man called Simon Weckert documented exactly how this feature worked by using a small cart full of Android phones in 2020.

And if Google knows your position, it almost certainly knows how you got there and where you’re heading next. It’s able to predict your habits, if you have any, and it might even have some idea of what your driving style is like. Google’s data usage patterns are more nebulous than most, so while the company has driving data, it’s not always clear what it’s used for. Self-driving car project Waymo might have been given a boost by user data. Real-world traffic information would prove very useful when training a self-driving AI.

Driving data mad

The above examples are just those who got there early. Access to data surrounding driving habits is of interest to just about everyone in the automotive space. As with every new source of data, there’s little regulation governing information collection in this sphere. Car-makers are, largely, hoarding this information, while outside sources are keen on it. How it is collected and when it may be shared should be ironed out now, before this additional source of user data becomes commonplace.

At present, driving data is either opt-in (no matter how vague education on the matter may be) or confined to expensive luxury vehicles. But it won’t be too long before every motor vehicle is a rolling WiFi hotspot, and at that point, the market for this data will explode. Keeping the people who generate it involved and informed of what they’re providing and to who will be of major importance in the future. As with every other form of user data, the average people should be aware of just how valuable they are to… pretty much everyone keeping a watching eye on their every movement.