Earlier this week Roscomsos, the Russian space agency, performed the latest of many (so many) International Space Station (ISS) resupply missions. The launch vehicle behind that trip to the ISS was the Soyuz 2.1a. It’ll also take centre stage later this month when it sends the replacement Soyuz MS-23 capsule to the space station.

Soyuz rockets (Soyuz means ‘union’) have been the backbone of Russia’s space program since 1966. The Soyuz 2.1a has been in service since 2004, alongside the 2.1b (2006) and 2.1v (2013). The difference between these? The ‘b’ variant is capable of heavier lift and the ‘v’ is a more lightweight orbital solution. The 2.1a came about when an analogue flight control system was upgraded to a digital one (allowing for in-flight launch adjustments) and efficiency improvements were implemented in the Soyuz-U’s engines.

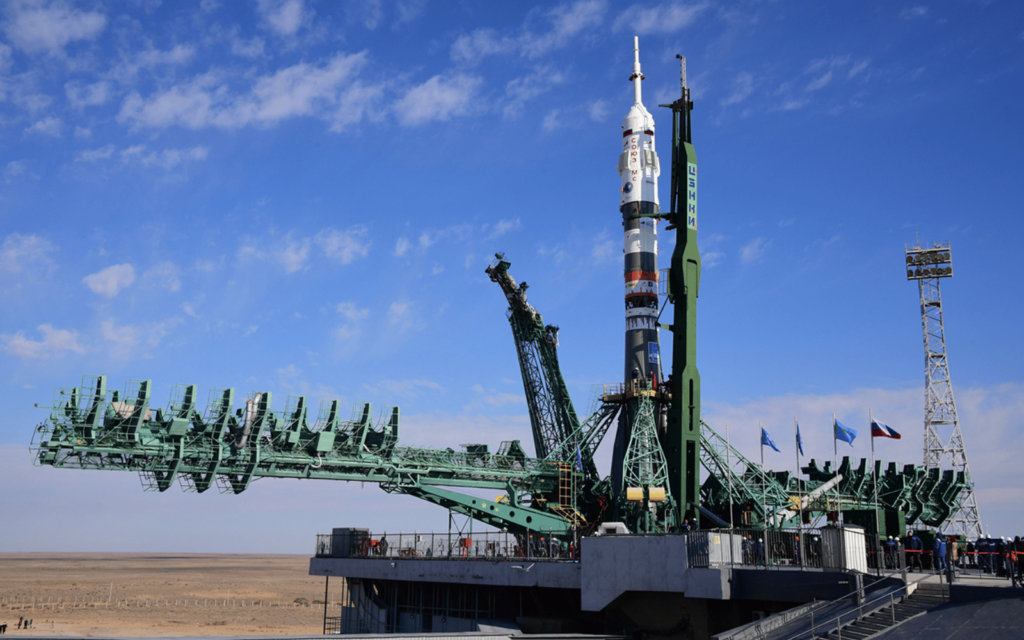

This is the Soyuz 2.1a

Russia’s rocket technology has long been the vehicle of choice when it comes to heading to the ISS. They’re not quite as refined as SpaceX‘s solutions, which are designed to be recovered and reused. Roscosmos, fields single-use hardware designed to send large payloads (up to 7 tonnes, in the case of the Soyuz 2.1a) into a low-Earth orbit (LEO). It’s capable of sending lesser loads into a geostationary orbit too.

The 2.1a launches from a pad at the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan. Unlike NASA’s launch sites, which are mostly coastal, the Kazakhstan launchpad is landlocked. Soyuz boosters, rather than crashing into the ocean, tend to come down on the Kazakhstan steppes. There tends to be nothing left to recover after a typical launch.

Russia’s workhorse is made up of three distinct sections. The first stage is composed of four RD-107A engines. These 19.6-metre boosters were originally designed for the R-7 Semyorka intercontinental ballistic missile. The second stage, the RD-108A, has a similar Cold War pedigree. Finally, the third stage of this 46.3-metre tall rocket is powered by the RD-0110. This engine, amazingly, was actually designed to act as the final stage of the Soyuz rockets. It is, unsurprisingly, still closely related to the engines originally created to send radioactive death to the American continent.

Not much living room

The 5 February Soyuz 2.1a launch sent up a Russian Progress spacecraft. Think of it as the space equivalent of that thing on the back of a Mr D driver’s bike, only much larger and capable of orbital reentry. These units are designed to be reusable and consist of three sections; the propulsion system, fuel compartment, and the freight area where the supplies destined for the ISS are stored. Progress MS-22, launched on Sunday, 5 February, carried 1,354 kilograms of dry goods (food, clothing, equipment, and experiments), 720kg of liquid propellant, 420kg of water, and 40kg of air.

Later this month, on 20 February, the Soyuz 2.1a will travel back to the International Space Station. This uncrewed mission will send a replacement crew module — the Soyuz MS-23 — to take the place of the leaking Soyuz MS-22. The damaged module will make an unmanned reentry while the new module sticks around for when its crew needs to head home.

The Soyuz capsule is largely similar to the Progress cargo container. It’s also composed of three sections but these are used very differently. The orbital module is used as living quarters by astronauts when it’s docked to the ISS. The middle section is the reentry module, a cramped area where the astronauts are packed before they drop nearly 410km to Earth. Finally, there’s the service module which hosts engines, life support, solar panels, and all the other technological accoutrements required for existing in space. Only the reentry section is designed to be reused. The orbital and service modules don’t survive reentry.