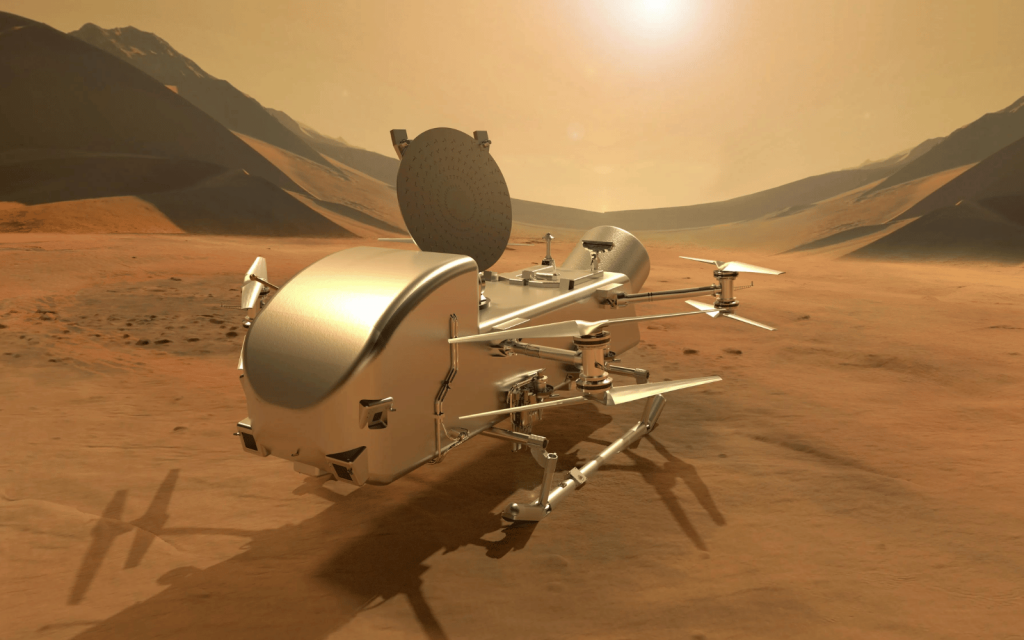

Human exploration of the solar system will be greatly assisted by machines like NASA’s Dragonfly. It’s not the first time we’ve heard its name, nor is it the first time we’ve been made aware of its mission. Dragonfly is intended to travel to Saturn’s moon, Titan, to explore the surface of the moon, the methane cycle there, and maybe to locate some alien life.

That last point isn’t the main point but even Arthur C. Clarke was of the opinion that Titan was a great candidate for alien life. The satellite hosts water, weather, and methane, otherwise known as rocket fuel. Exploration of deeper space will rely heavily on exploiting that region and Dragonfly is the vehicle that will examine the possibility of doing that.

Enter the Dragonfly

At the moment, NASA’s rotorcraft lander is undergoing testing in a series of wind tunnels the space agency has access to. Unlike the sort of wind tunnel your shiny new car or an aircraft wing will be tested in, these simulate the conditions of atmospheres that don’t exist on this planet. These facilities, located at NASA’s Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, host the Subsonic and Transonic Dynamics Tunnel (TDT).

Of these, the TDT is able to simulate Titan’s nitrogen-rich atmosphere. The tests, conducted with a half-sized version of the final Dragonfly craft, determine how the stacked rotor configuration will handle the moon’s atmosphere. The point is to see the phenomenal success the Mars Ingenuity helicopter has experienced.

Rick Heisler, Dragonfly’s wind tunnel test lead from Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), explains, “The heavy gas environment in the TDT has a density three-and-a-half times higher than air while operating at sea level ambient pressure and temperature.”

“This allows the rotors to operate at near-Titan conditions and better replicate the lift and dynamic loading the actual lander will experience. The data we acquire are used to validate predictions of the lander aerodynamics, aero-structural performance, and rotor fatigue life in the harsh cryogenic environment on Titan.”

What we’re most excited about is the nuclear engine that will drive this one when it eventually makes landfall (planetfall?) in the next decade but that information is still under wraps. The New Frontiers mission that will send Dragonfly to Titan will lift off no sooner than 2027 and it’ll probably be delayed unless everything goes perfectly.

Should it make its deadline, the craft will reach Titan around 2035. Ken Hibbard, of the Johns Hopkins APL, said, “The mission is coming together piece by piece, and we’re excited for every next step toward sending this revolutionary rotorcraft across the skies and surface of Titan.”