We live in a world in which momentous decisions are made by people often without forethought. But some things are predictable, including that if you continually consume a finite resource without recycling, it will eventually run out.

Yet, as we set our sights on embarking back to the moon, we will be bringing with us all our bad habits, including our urge for unrestrained consumption.

Since the 1994 discovery of water ice on the moon by the Clementine spacecraft, excitement has reigned at the prospect of a return to the moon. This followed two decades of the doldrums after the end of Apollo, a malaise that was symptomatic of an underlying lack of incentive to return.

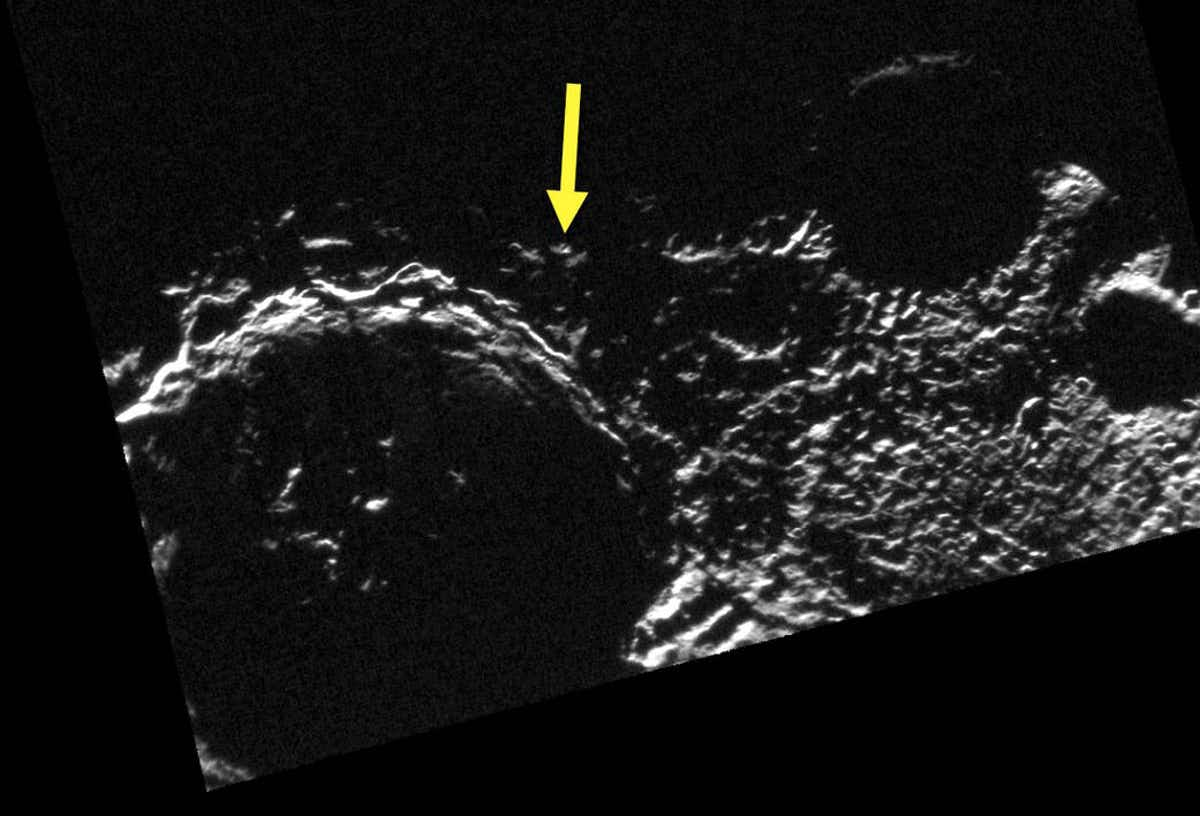

That water changed everything. The water ice deposits are located at the poles of the moon hidden in the depths of craters that are forever devoid of sunlight.

Since then, not least due to the International Space Station, we have developed advanced techniques that allow us to recycle water and oxygen with high efficiency. This makes the value of supplying local water for human consumption more tenuous, but if the human population on the Moon grows so will demand. So, what to do with the water on the moon?

There are two commonly proposed answers: energy storage using fuel cells and fuel and oxidizer for propulsion. The first is easily dispensed with: fuel cells recycle their hydrogen and oxygen through electrolysis when they are recharged, with very little leakage.

Energy and fuel

The second — currently the primary raison d’être for mining water on the moon — is more complex but no more compelling. It is worth noting that SpaceX uses a methane/oxygen mix in its rockets, so they would not require the hydrogen propellant.

So, what is being proposed is to mine a precious and finite resource and burn it, just like we have been doing with petroleum and natural gas on Earth. The technology for mining and using resources in space has a technical name: in-situ resource utilization.

And while oxygen is not scarce on the moon (around 40 per cent of the moon’s minerals comprise oxygen), hydrogen most certainly is.

Extracting water from the moon

Hydrogen is highly useful as a reductant as well as a fuel. The moon is a vast repository of oxygen within its minerals but it requires hydrogen or other reductant to be freed.

For instance, ilmenite is an oxide of iron and titanium and is a common mineral on the moon. Heating it to around 1,000 C with hydrogen reduces it to water, iron metal (from which an iron-based technology can be leveraged) and titanium oxide. The water may be electrolyzed into hydrogen — which is recycled — and oxygen; the latter effectively liberated from the ilmenite. By burning hydrogen extracted from water, we are compromising the prospects for future generations: this is the crux of sustainability.

But there are other, more pragmatic issues that emerge. How do we access these water ice resources buried near the lunar surface? They are located in terrain that is hostile in every sense of the word, in deep craters hidden from sunlight — no solar power is available — at temperatures of around 40 Kelvin, or -233 C. At such cryogenic temperatures, we have no experience in conducting extensive mining operations.

Peaks of eternal light are mountain peaks located in the region of the south pole that are exposed to near-constant sunlight. One proposal from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Lab envisages beaming sunlight from giant reflectors located at these peaks into craters.

These giant mirrors must be transported from Earth, landed onto these peaks and installed and controlled remotely to illuminate the deep craters. Then robotic mining vehicles can venture into the now-illuminated deep craters to recover the water ice using the reflected solar energy.

Water ice may be sublimed into vapour for recovery by direct thermal or microwave heating – because of its high heat capacity, this will consume a lot of energy, which must be supplied by the mirrors. Alternatively, it may be physically dug out and subsequently melted at barely more modest temperatures.

Using the water

After recovering the water, it needs to be electrolyzed into hydrogen and oxygen. To store them, they should be liquefied for minimum storage tank volume.

Although oxygen can be liquefied easily, hydrogen liquefies at 30 Kelvin (-243 C) at a minimum of 15 bar pressure. This requires extra energy to liquefy hydrogen and maintain it as liquid without boil-off. This cryogenically cooled hydrogen and oxygen (LH2/LOX) must be transported to its location of use while maintaining its low temperature.

So, now we have our propellant stocks for launching stuff from the moon.

This will require a launchpad, which may be located at the moon’s equator for maximum flexibility of launching into any orbital inclination as a polar launch site will be limited to polar launches — to the planned Lunar Gateway only. A lunar launchpad will require extensive infrastructure development.

In summary, the apparent ease of extracting water ice from the lunar poles belies a complex infrastructure required to achieve it. The costs of infrastructure installation will negate the cost savings rationale for in-situ resource utilization.

Alternatives to extraction

There are more preferable options. Hydrogen reduction of ilmenite to yield iron metal, rutile and oxygen provides most of the advantages of exploiting water. Oxygen constitutes the lion’s share of the LH2/LOX mixture. It involves no great infrastructure: thermal power may be generated by modest-sized solar concentrators integrated into the processing units. Each unit can be deployed where it is required – there is no need for long traverses between sites of supply and demand.

Hence, we can achieve almost the same function through a different, more readily achievable route to in-situ resource utilization that is also sustainable by mining abundant ilmenite and other lunar minerals.

Let us not keep repeating the same unsustainable mistakes we have made on Earth — we have a chance to get it right as we spread into the solar system.

- is Professor, Canada Research Chair in Space Robotics and Space Technology, Carleton University

- This article first appeared on The Conversation