Didn’t we say that 2021 was space’s year? NASA has two new exploration projects on the boil: Lucy, a spacecraft launching this year with plans to explore the Jupiter Trojan asteroids and the Dragonfly, which is set to take off in 2027 bound for Saturn’s moon Titan.

Lucy goes first

Lucy has a 23-day launch window this year, starting on 16 October. The Lockheed Martin-created spacecraft itself was dropped off at the Kennedy Space Center at the end of July. It’s set to undergo final checks and fuelling but, once that hurdle is passed, it’ll be blasting off on a twelve-year mission to explore Jupiter’s Trojan asteroid, which are remnants of our early solar system orbiting with our gas giant in two ‘swarms’.

The point is to survey what are essentially celestial fossils in our solar system to see what we can learn about them. hence the name of the mission. Once Lucy finishes its mission in 2033, it’ll remain in its orbit long enough to become a fossil itself — possibly millions of years — which is why the team working on it opted to include a time capsule on the craft, which includes a depiction of the solar system’s configuration on its expected day of launch so it can be dated by whoever discovers it.

Dragonfly spreads its wings in 2027

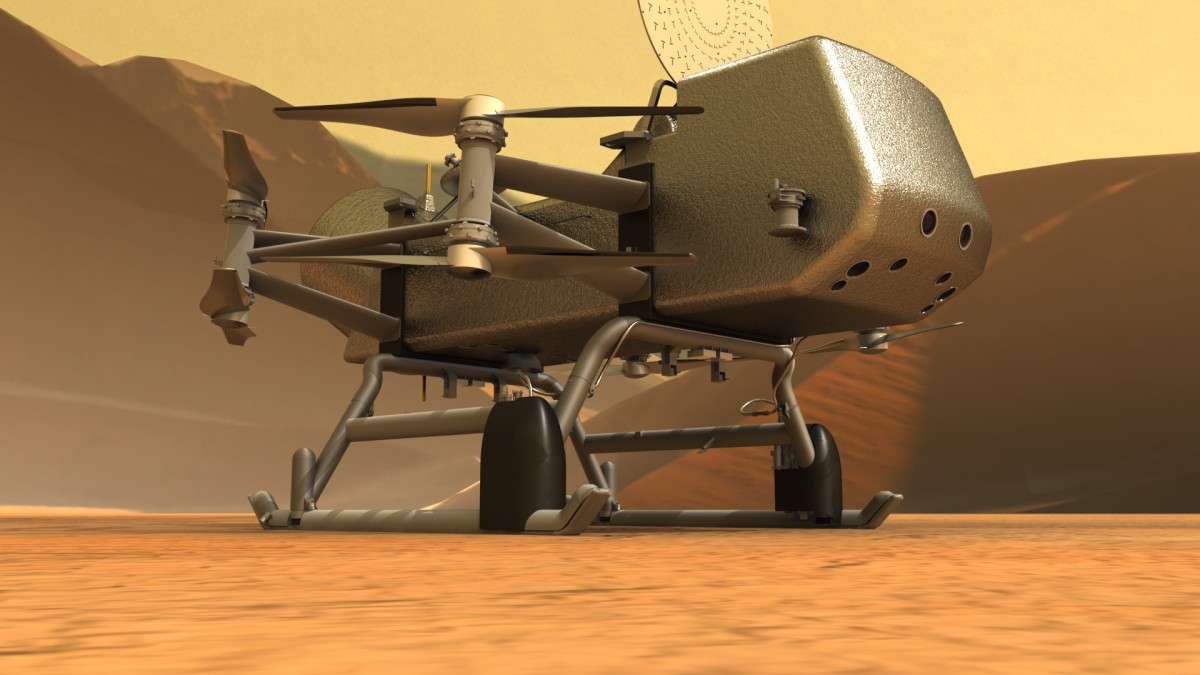

Also heading out in that direction, but with a few years to go before it actually takes off, is Dragonfly. This well-named craft is bound for Titan, one of the moons of Saturn, where it’ll be the first craft to actually explore the moon’s surface. Titan is unique in that it’s got a similar structure to Earth — there’s water and weather, though it rains methane… which is just another reason that space agencies have their eye on Titan. It’d be an ideal refuelling station for deeper manned space exploration.

Dragonfly is a rotorcraft relocatable lander inspired by the success of NASA’s Ingenuity mission to Mars this year. Since it’s been proved that we can fly drones on other planets, sending something like Dragonfly to explore the surface of one of the most enticing celestial bodies in our solar system makes a whole lot of sense.

“Titan represents an explorer’s utopia,” said Alex Hayes, associate professor of astronomy in the College of Arts and Sciences and a Dragonfly co-investigator. “The science questions we have for Titan are very broad because we don’t know much about what is actually going on at the surface yet. For every question we answered during the Cassini mission’s exploration of Titan from Saturn orbit, we gained 10 new ones.”

Dragonfly will check out Titan’s methane cycle, the prebiotic chemistry between its atmosphere and surface and it’ll also check for biochemical signatures — which sounds an awful lot like it’s looking for signs of life. As well it should. If we’re going to find life anywhere in our solar system, it’ll be on another planet with water.