What does it mean to be an inventor?

In patent law, designed to protect the intellectual property of inventors, officials are used to thinking of inventors as humans, taking an “inventive step” – a new way of doing something — not obvious to a person skilled in the same art.

But last week — in a judicial world first — Australia’s Federal Court ruled an artificial intelligence (AI) system can be named as an inventor.

That judgement overturned a decision by the nation’s Commissioner of Patents that meant US scientist Stephen Thaler could not patent inventions by his AI system, DABUS (Device for Autonomous Bootstrapping of Unified Sentience).

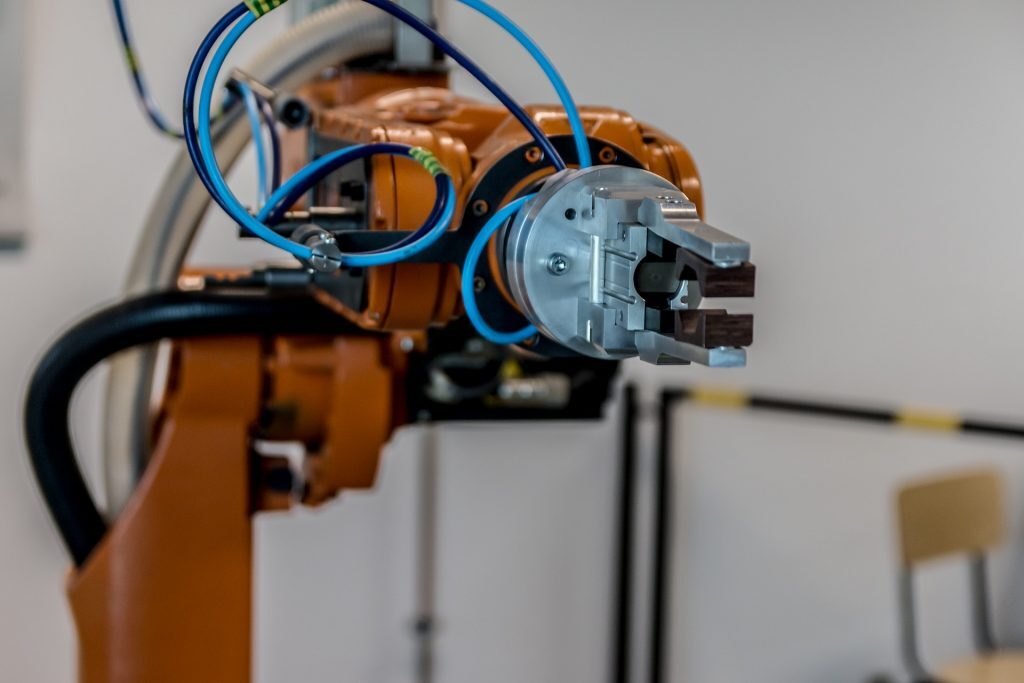

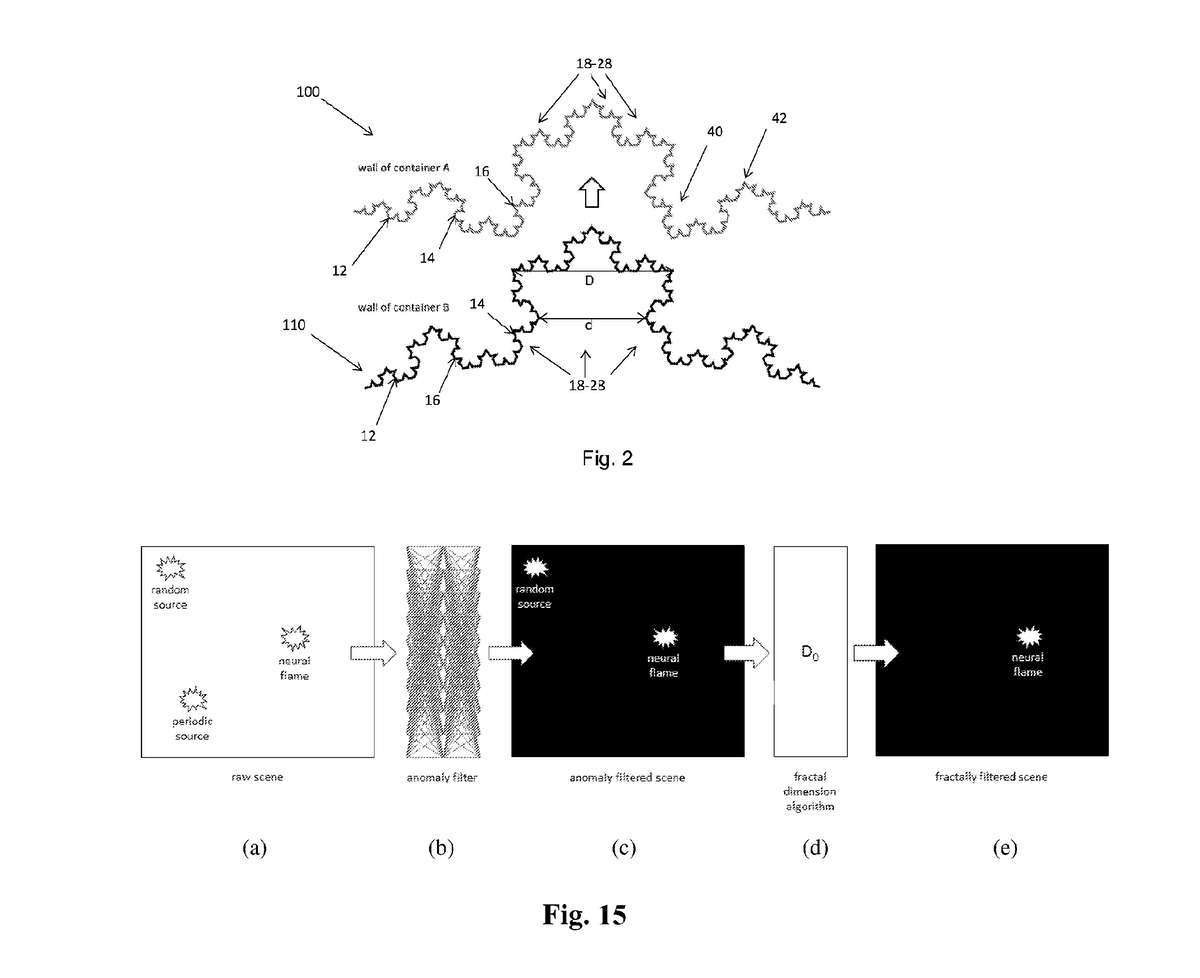

Thaler says DABUS independently designed a fractal-shaped container for improved grip and heat transfer, and an emergency beacon that flashes more noticeably. So he can’t take credit as the actual inventor.

He has filed patent applications in 17 countries, as permitted by the international Patent Cooperation Treaty. In the US, UK, Germany, Europe and Australia, the patent offices have not approved them. Patent office decisions are pending in 11 other countries.

Just one patent office has granted the patent: South Africa’s Companies and Intellectual Property Commission, which published the Thaler patent on July 28, two days before the Australian Federal Court ruling.

So Australia is not the world’s first nation to allow a machine to be named as inventor. But the South African patent office granted the patent because its practice prevented examination of inventorship and ownership.

Accordingly, the ruling of the Federal Court — to which Thaler appealed the Patent Commissioner’s decision — is a world first in terms of a court ruling in favour of AI as an inventor in its own right.

A machine can invent, but can’t own its invention

The specific reasons why most patent offices have rejected Thaler’s application differ according to the wording of legislation and how patents officials have interpreted the rules.

But there are some common themes. In the case of the UK and Australian patent offices, the main stumbling block was not that the examiners couldn’t accept a machine could invent something; it was that they did not see how a machine could own what it invented.

This issue of ownership is essential to the patent process. It requires, in cases where the applicant is different to the inventor, that the applicant show they have properly obtained ownership — or “title” — from the inventor.

The patent offices rejected Thaler’s application on the basis DABUS, as a machine, couldn’t “hold” title or pass it to Thaler, who didn’t want to name himself as the inventor because he didn’t do the inventing.

The English and Australian patent offices also argued the wording of their respective patent laws suggested an inventor needed to be human. The US and European offices also made this argument.

Why Australia’s Federal Court ruled for AI

But Australian Federal Court judge Jonathan Beach ruled, at least when it comes to Australia, this is not the case.

In overturning interpretation made by Australia’s Commissioner of Patents, Justice Beach said the patents legislation did not require the inventor to hold title, or pass it to the applicant. It simply required the applicant to receive title in a way the law recognises — like, for example, a dairy farmer receives “title” in their cows’ milk.

Thaler received title because he owned and controlled DABUS, its code, and he possessed DABUS’ output: the invention.

Justice Beach noted his interpretation served the rationale of the Patents Act, which is to incentivise innovation. Without taking this view, the “odd outcome” would be that DABUS’ invention was not owned, and was unpatentable. There would therefore be a patent black hole for AI-generated inventions.

Fears of AI monopolising technology

For now, Justice Beach’s decision means Australia and South Africa are the only two countries in the world accepting AI as inventors.

That won’t necessarily be the case for long, depending on the outcome of Thaler’s UK legal challenge against the decision of the High Court of Justice. The Court of Appeal is due to hand down a decision on the appeal in October. Thaler is also making legal challenges against the decisions of the US Patent and Trademark Office and the European Patent Office.

If these other courts decide differently to Justice Beach, it could mean Australia and South Africa become beacons for the lodging of AI-invented patents. This would not be the bonus it might seem. It could leave local companies having to pay even more to use patented foreign inventions.

But what if other jurisdictions do follow Australia’s lead?

There are concerns that accepting machines as inventors could, as Melbourne Law School senior fellow Mark Summerfield has warned, create an avalanche of “automated patent generators” monopolising technology.

This would further entrench the dominance of tech companies for whom AI is central, such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Alibaba. As University College Cork economist Wim Naudé, has written, these platforms have a huge first-mover advantage in AI, “turning them into monopolists and gatekeepers”.

Summerfield has argued restricting the notion of invention to humans is the “primary legal barrier” to prevent this.

Phantom fears

But there are three reasons to agree with Justice Beach that such fears are a “phantom”.

First, to get a patent an invention must satisfy a stringent range of requirements. Applicants must prove, among other things, the invention has “worldwide novelty” and involves an inventive step.

Second, patents are expensive. It’s not like speculating on a domain name. The cost of a PCT patent in 10 jurisdictions is about A$150,000 plus maintenance fees. This is a big disincentive to abusing the patents system.

Finally, since 2019, patent owners are subject to anti-monopoly laws, so the competition watchdog, the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission, can take action against those seeking to abuse intellectual property rights to stifle competition.

So this patent decision is not AI-mageddon.

But as with all things AI, caution is prudent.

As the Open Letter on Artificial Intelligence signed by Stephen Hawking, Elon Musk and many others involved in AI research says, more research on AI needed “to reap its benefits while avoiding potential pitfalls”.

- is Postgraduate Research Coordinator, Senior Lecturer in Innovation & Intellectual Property Law, School of Business and Law, CQUniversity Australia

- This article first appeared on The Conversation