If like many Muslims you have reported hate speech to Facebook and received an automated response saying it doesn’t breach the platform’s community standards, you are not alone.

If like many Muslims you have reported hate speech to Facebook and received an automated response saying it doesn’t breach the platform’s community standards, you are not alone.

We and our team are the first Australian social scientists to receive funding through Facebook’s content policy research awards, which we used to investigate hate speech on LGBTQI+ community pages in five Asian countries: India, Myanmar, Indonesia, the Philippines and Australia.

We looked at three aspects of hate speech regulation in the Asia Pacific region over 18 months. First we mapped hate speech law in our case study countries, to understand how this problem might be legally countered. We also looked at whether Facebook’s definition of “hate speech” included all recognised forms and contexts for this troubling behaviour.

In addition, we mapped Facebook’s content regulation teams, speaking to staff about how the company’s policies and procedures worked to identify emerging forms of hate.

Even though Facebook funded our study, it said for privacy reasons it could not give us access to a dataset of the hate speech it removes. We were therefore unable to test how effectively its in-house moderators classify hate.

Instead, we captured posts and comments from the top three LGBTQI+ public Facebook pages in each country, to look for hate speech that had either been missed by the platform’s machine intelligence filters or human moderators.

Admins feel let down

We interviewed the administrators of these pages about their experience of moderating hate, and what they thought Facebook could do to help them reduce abuse.

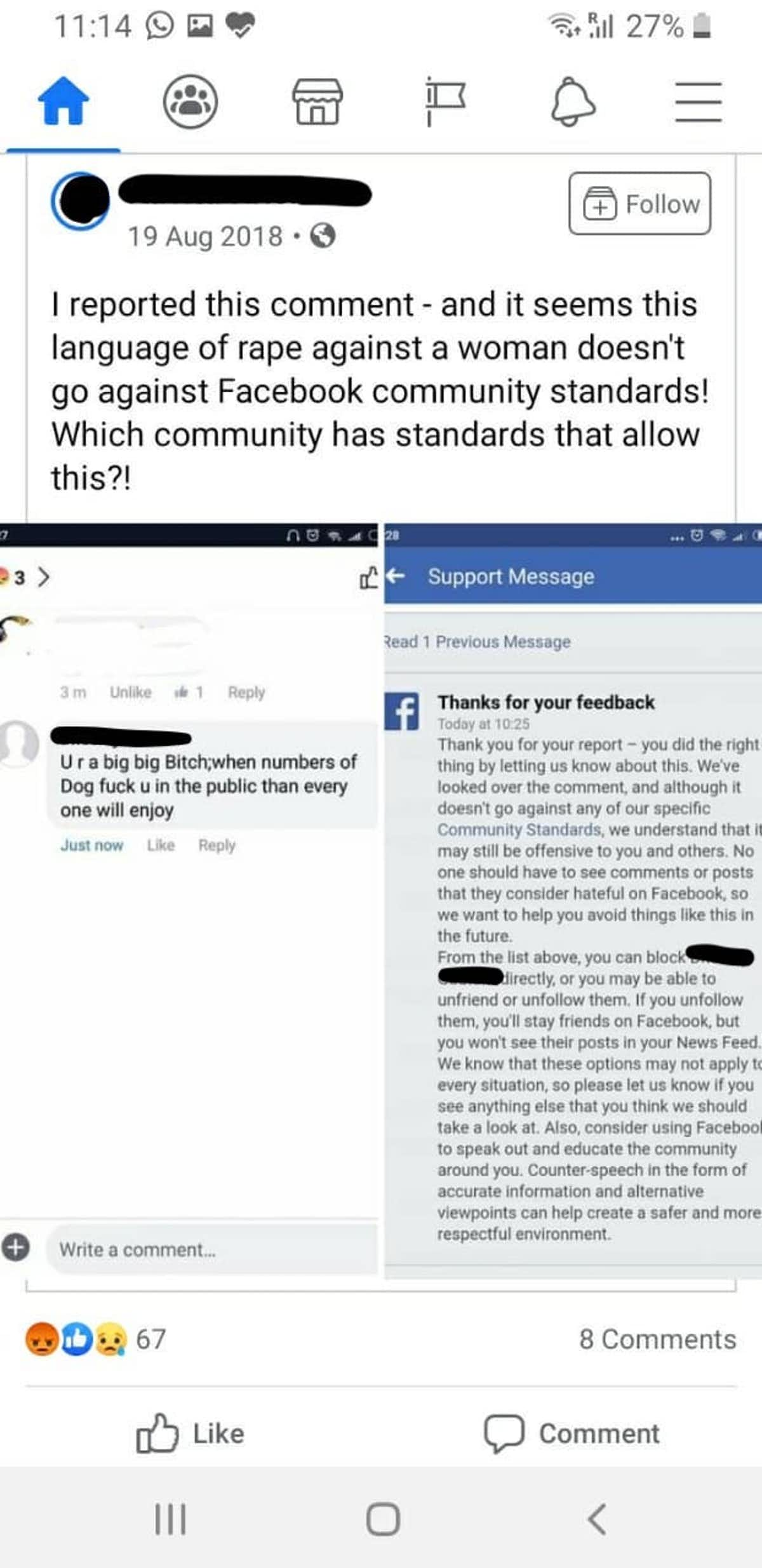

They told us Facebook would often reject their reports of hate speech, even when the post clearly breached its Community Standards. In some cases messages that were originally removed would be re-posted on appeal.

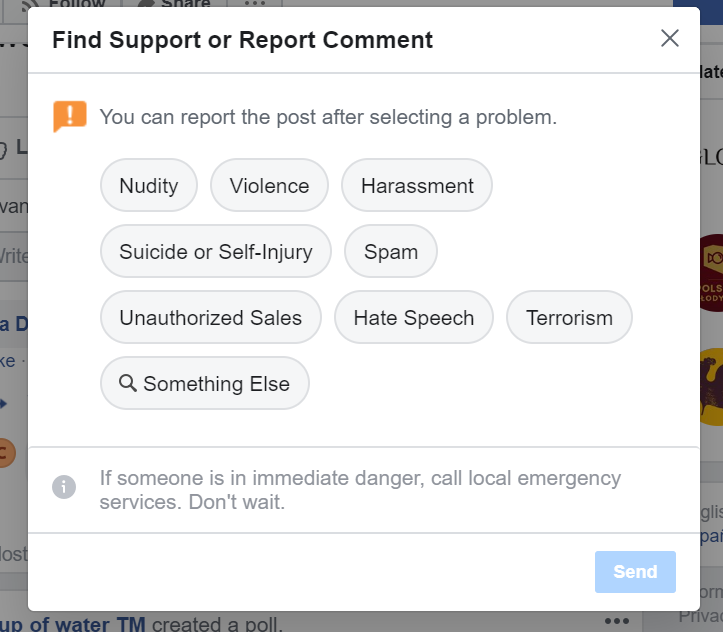

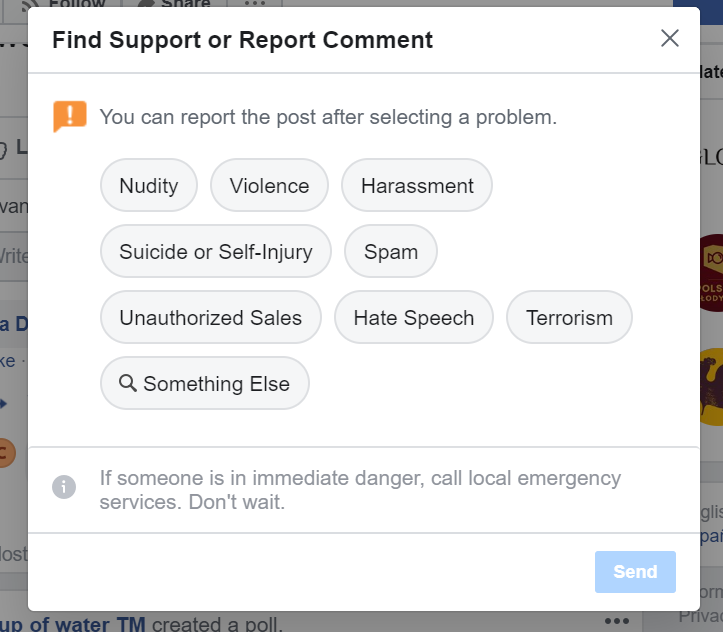

Most page admins said the so-called “flagging” process rarely worked, and they found it disempowering. They wanted Facebook to consult with them more to get a better idea of the types of abuse they see posted and why they constitute hate speech in their cultural context.

Defining hate speech is not the problem

Facebook has long had a problem with the scale and scope of hate speech on its platform in Asia. For example, while it has banned some Hindu extremists, it has left their pages online.

However, during our study we were pleased to see that Facebook did broaden its definition of hate speech, which now captures a wider range of hateful behaviour. It also explicitly recognises that what happens online can trigger offline violence.

It’s worth noting in the countries we focused on, “hate speech” is seldom precisely legally prohibited. We found other regulations such as cybersecurity or religious tolerance laws could be used to act against hate speech, but instead tended to be used to suppress political dissent.

We concluded that Facebook’s problem is not in defining hate, but being unable to identify certain types of hate, such as that posted in minority languages and regional dialects. It also often fails to respond appropriately to user reports of hate content.

Where hate was worst

Media reports have shown Facebook struggles to automatically identify hate posted in minority languages. It has failed to provide training materials to its own moderators in local languages, even though many are from Asia Pacific countries where English is not the first language.

In the Philippines and Indonesia in particular, we found LGBTIQ+ groups are exposed to an unacceptable level of discrimination and intimidation. This includes death threats, targeting of Muslims and threats of stoning or beheading.

On Indian pages, Facebook filters failed to capture vomiting emojis posted in response to gay wedding photos, and rejected some very clear reports of vilification.

In Australia, on the other hand, we found no unmoderated hate speech – only other types of insensitive and inappropriate comments. This could indicate less abuse gets posted, or there is more effective English language moderation from either Facebook or page administrators.

Similarly in Myanmar LGBTIQ+ groups experienced very little hate speech. But we are aware Facebook is working hard to reduce hate speech on its platform there, in the wake of it being used to persecute the Rohingya Muslim minority.

Also, it’s likely gender diversity isn’t as volatile a subject in Myanmar as it is in India, Indonesia and the Philippines. In these countries LGBTIQ+ rights are highly politicised.

Facebook has taken some important steps towards tackling hate speech. However we’re concerned COVID-19 has forced the platform to become more reliant on machine moderation. That too at a time when it can only automatically identify hate in around 50 languages – even though thousands are spoken everyday across the region.

What we recommend

Our report to Facebook outlines several key recommendations to help improve its approach to combating hate on its platform. Overall, we have urged the company to convene more regularly with persecuted groups in the region, so it can learn more about hate in their local contexts and languages.

This needs to happen alongside a boost to the numbers of its country policy specialists and in-house moderators with minority language expertise.

Mirroring efforts in Europe, Facebook also needs to develop and publicise its trusted partners channel. This provides visible, official hate speech-reporting partner organisations through which people can directly report hate activities to Facebook during crises such as the Christchurch mosque attacks.

More broadly, we would like to see governments and NGOs cooperate to set up an Asian regional hate speech monitoring trial, similar to one organised by the European Union.

Following the EU example, such an initiative could help identify urgent trends in hate speech across the region, strengthen Facebook’s local reporting partnerships, and reduce the overall incidence of hateful content on Facebook.

- is Associate Professor in Convergent and Online Media, University of Sydney

- is Lecturer in Government and International Relations, University of Sydney

- This article first appeared on The Conversation