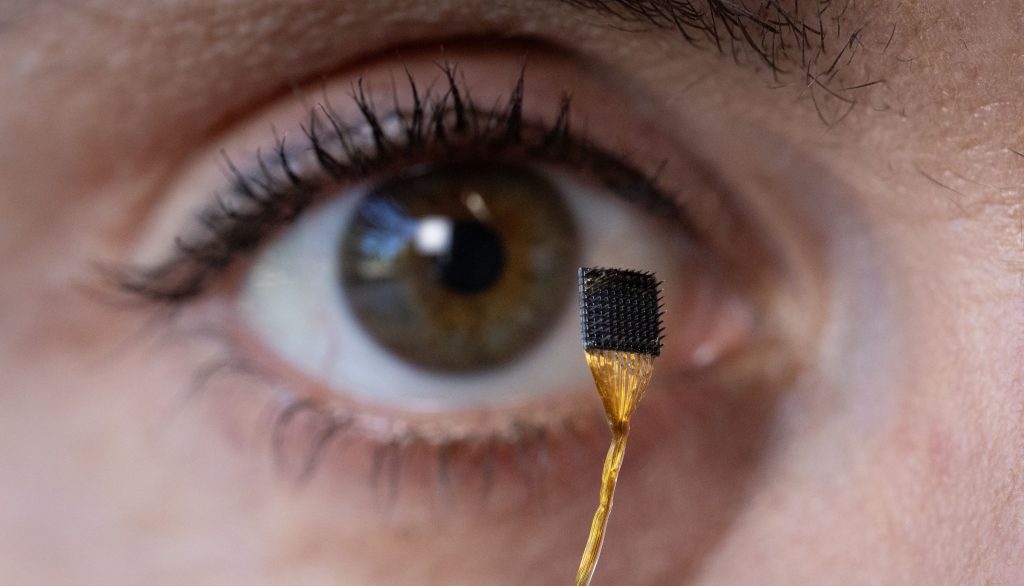

Stanford Medicine researchers have been working on a new brain-computer interface (BCI) chip intended to restore speech to folks who have severe difficulties verbalising anything. The implantable BCI lives in a subject’s motor cortex — the area that controls movement — and collects signals when patients attempt to speak. These are then translated into speech via a computer algorithm.

The process works by training a computer to “recognize repeatable patterns of neural activity associated with each “phoneme” — the tiniest units of speech — then stitch[ing] the phonemes into sentences.” The principle works when patients attempt to physically speak, capturing muscle twitches as well as brain impulses, but Stanford’s team has also made inroads into capturing so-called “inner speech.”

Stanford that new stream

You might be more familiar with the term ‘inner monologue‘, the internal voice heard when thinking. Stanford’s Frank Willett, the co-director of the institution’s Neural Prosthetics Translation Laboratory, explains that “We found that inner speech evoked clear and robust patterns of activity in these brain regions. These patterns appeared to be a similar, but smaller, version of the activity patterns evoked by attempted speech.”

“We found that we could decode these signals well enough to demonstrate a proof of principle, although still not as well as we could with attempted speech.”

It’s a great idea for paralysed patients and other people with physical impairments, but the institute also seems keenly aware of the potential privacy implications. Having a BCI chip installed could lead to inner thoughts, which are sometimes not intended to be shared, becoming impossible to hide. At least, in theory. Willett points out that the technology they’re exploring is in its infancy.

“[I]mplanted BCIs are not yet a widely available technology and are still in the earliest phases of research and testing. They’re also regulated by federal and other agencies to help us to uphold the highest standards of medical ethics.”

The tech might be in the early stages, but the existence of government entities in the picture could be more concerning than a wholly independent effort on Stanford’s part. Few groups, beyond the major data miners like Google, Meta, and others like them, exceed governments when it comes to poking around what people might be thinking. The UK already arrests people for posting comments on social media; it’s no stretch to believe that such a device would give them the ability to conduct arrests for ‘incorrect’ thoughts.

But, as with most brain-computer interface research, the work being done by Stanford is ultimately supposed to be altruistic. At least a few years remain before the technology is refined enough for specialist use, with commercial implementations not even in sight. But if you find yourself black-bagged by your authoritarian government overlords and wake up with a throbbing head and a fresh scar in your skull, try not to think too hard about it.