It took a while for us to get here. Once upon a time, Google was the very best internet search engine on the planet. That wasn’t hard to do in the 1990s, but it managed to retain its position right up until it placed current Chief Technologist Prabhakar Raghavan in charge of ads and commerce at the company in 2018. It wasn’t all Raghavan’s fault. The company had been in a downward slide for some time before that, but that point marks the moment when Google explicitly cared more about money than about making a decent product.

The search giant’s slide into enshittification was already on the cards, but someone (I’ve got a sneaky suspicion who) inside Google stomped on the gas around 2018, making almost every product actively worse. Sure, Maps will still tell you where you’re going, and Gmail still lets you receive messages from those folks who still care, but how much pointless crap did you have to wade through to get to those basic functions? And that was before the rise of AI and Gemini, which actively and (seemingly) intentionally limits your access to information so that you’ll use this new technology to do things… less effectively than you would have ten years ago.

It’s time for a history lesson. In the early days of the internet, people — regular people, sure, but mostly passionate people — were motivated to create and host information on the fledgling internet about subjects they cared about. There wasn’t much call for fact-checking, because those regular folks cared about the information they compiled. Also, the advertisers hadn’t figured out how to use the internet yet. Google… Google was the absolute best thing to use to a) find information about those subjects and b) source new pots of knowledge that you never even suspected existed.

Some of those places still exist, but it’s a pain in the ass to find them. All they have is relevant information, much of it personal, but there’s little to no possibility of converting your web search into a sale or a view or something else that generates revenue. So you’re not allowed to access them via Google or any other search engine. It’s probably not something that’s done on purpose. The definition of a ‘useful’ website has changed over the years, but most of them… aren’t. Useful, that is.

What use is Facebook? How about Instagram? Twitter? (Calm down, Elon, this is a history lesson, remember?) Google itself? Where else do you go regularly? I’m willing to bet that, if you’re an internet user of a certain age, the number of ‘regular’ locations you go to has dropped dramatically since the days before the internet was a consumer hellscape of ads and influencers and attempts to control how you think about pretty much everything. You can thank platforms for that.

Platforms are central locations where information is gathered, so you don’t have to look for it. That’s handy, in one sense. Takes less time. But it’s also a nexus for control. The folks at Wikipedia don’t like an opinion? Your speech threatens a company’s bottom line? Well, then you won’t appear on the platform.

Since those things have been growing and absorbing and consuming for about two decades, that’s a lot of curated data in a single place. There’s also a metric fuckton that’s excluded, because it doesn’t fit there. It won’t make money. It won’t drive engagement. All it does is sit there and be useful, and nobody who controls a platform wants that. The platform is supposed to be useful. Nothing else exists. And if you think it ever did, you’re delusional.

Once upon a time, Google would surface every website that contained the words you specified in a search. These were ranked, more or less, and they could be gamed, but that was only a problem after money arrived on the internet, looking for a larger bottom line. Even so, for a long time, you got what you searched for. More than you searched for, in fact. It took at least some discernment to figure out which information was relevant and which was made up, but generally, genuine information was obvious.

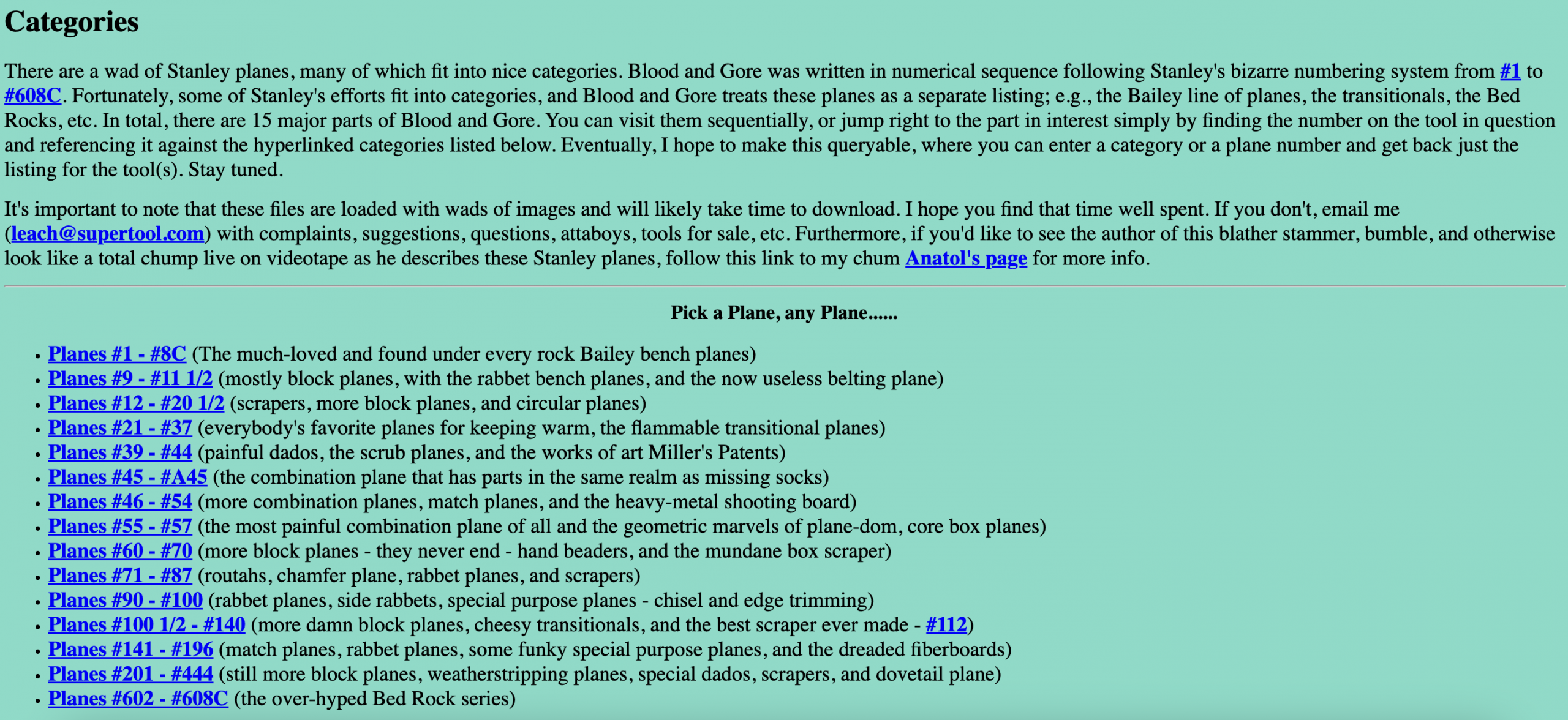

I’ll give you a few concrete examples. Back in the early days, before Google fell into its current money pit, the internet was populated with websites like this one. This website, Supertool, is the work of Patrick A. Leach. It lists, as far as can be discerned, detailed information about the design, manufacture, and sale of Stanley hand planes in America. It’s a niche subject, sure, but it’s also the most complete repository of its type I’ve been able to locate. It represents a lot of searching and leaping over obstacles put in place by search engines, who just… don’t want me there. It’s not good for business.

I’ll give you a few concrete examples. Back in the early days, before Google fell into its current money pit, the internet was populated with websites like this one. This website, Supertool, is the work of Patrick A. Leach. It lists, as far as can be discerned, detailed information about the design, manufacture, and sale of Stanley hand planes in America. It’s a niche subject, sure, but it’s also the most complete repository of its type I’ve been able to locate. It represents a lot of searching and leaping over obstacles put in place by search engines, who just… don’t want me there. It’s not good for business.

A more modern take on woodwork information is Paul Sellers’ blog and YouTube channel. Sellers is a rare example of this sort of information modernised and even monetised, but his work is not as single-minded as the other internet lunatics from days of yore are known for. It’ll still die with him, as will other websites.

Websites like Fernglas Museum, run by a German obsessive called (I think) Johann Leichtfried. You’ll find few resources concerning vintage binoculars better than this one on the internet. A similar website, run by one Ulrich Zeun, covers vintage and modern monoculars. A third covers very small optics. Despite its design rivalling the TimeCube website, it’s packed with subject-specific information you just can’t find anywhere else. Heck, here’s a website with a selection of Japanese optics catalogues from the mid-to-late 20th Century. You have no idea how hard that was to locate.

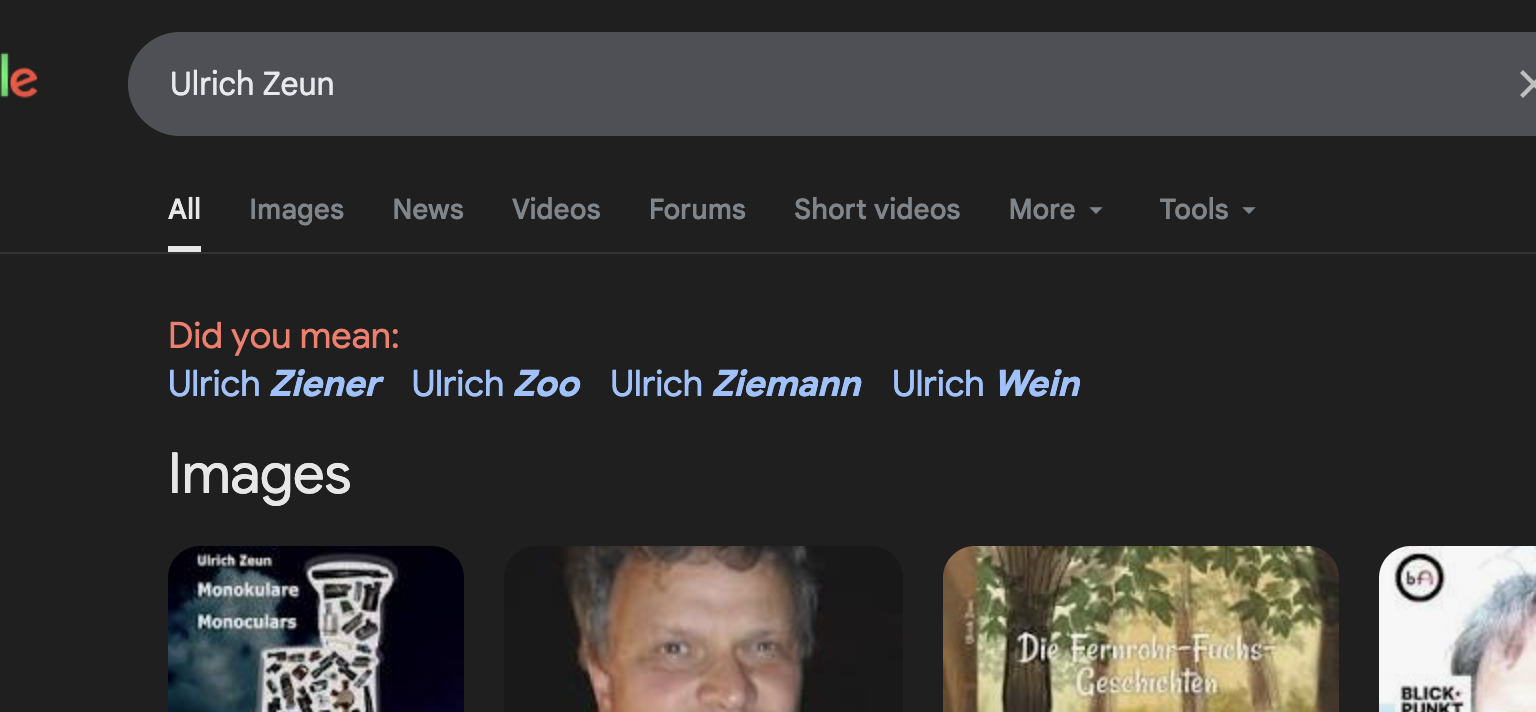

These websites cover my own personal obsessions, but you must understand that the internet was once populated by these information sources across a massive spectrum. No matter your subject, someone knew something and was willing to share it. They used to be easy to locate and explore. These places are amazingly helpful if you’re looking to learn about something, but they’re not profitable. That’s why search engines like Google only surface them when you force them to, if at all. Searching for ‘Ulrich Zeun’ confuses Google, which offers a selection of alternatives (above) that benefit the search company rather than just showing you what you want to see.

These websites cover my own personal obsessions, but you must understand that the internet was once populated by these information sources across a massive spectrum. No matter your subject, someone knew something and was willing to share it. They used to be easy to locate and explore. These places are amazingly helpful if you’re looking to learn about something, but they’re not profitable. That’s why search engines like Google only surface them when you force them to, if at all. Searching for ‘Ulrich Zeun’ confuses Google, which offers a selection of alternatives (above) that benefit the search company rather than just showing you what you want to see.

Is it possible to go back to a time where the internet was considered “all the sentiments and expressions of humanity, from the debasing to the angelic, […] parts of a seamless whole, the global conversation of bits,” as Electronic Frontier Foundation founder John Perry Barlow described it in 1996? Probably not. Certainly not without resorting to building a parallel internet (they tried that, it’s called the dark web, and it’s for… less than legal things), or without convincing the world at large that the convenience offered by Google, Meta, Amazon, Microsoft, and all the massive companies attempting to assimilate the internet into themselves is a poor substitute for the free flow of information.

But it’s definitely worth remembering the promise the internet once held: Messy, unattractive, wildly disorganised, but also packed with reams of knowledge. In short, it used to be a thoroughly human thing. Now? It’s just a thing that makes money for companies like Google that sit on top of it.