When the International Astronomical Union announced in 2006 that Pluto was being demoted from its status as the Sun’s ninth planet, many astronomers and non-experts alike were shocked.

Pluto remains an important object for study, though. Today it is considered one of many dwarf planets beyond Neptune, in a doughnut-shaped region of mostly icy debris orbiting the Sun called the Kuiper Belt. These outskirts of the solar system remain largely unexplored. They were first reached by US space agency NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft; it flew close to Pluto in 2015, revealing spectacular images of the dwarf planet’s surface and atmosphere. But there’s still plenty to learn.

That’s why my colleagues and I at South Africa’s University of the Western Cape (UWC) were over the moon when we were invited to participate in an international mission funded by NASA. We are a group of experienced nuclear physicists with groundbreaking research that spans astronomy and stellar explosions.

Pluto reached its closest point to our Sun in 1989. As it moves away from the Sun along its 248-year-long oval-shaped orbit, its atmosphere will likely collapse and freeze onto its surface in the next few years.

We were asked to observe a rare event that would provide insights into the dwarf planet’s atmosphere and particularly this likely freezing scenario. The event is called occultation, and occurs when any celestial object passes in front of a distant star, temporarily blocking or dimming the star’s light. This allows the object’s atmosphere to – just for a second or so – act as a lens that amplifies the starlight. In this case, the occultation was a chance to capture information about Pluto’s atmosphere, as explained below.

A single telescope

We used a single state-of-the-art 0.5-metre Newtonian telescope that was generously donated to UWC by the University of Virginia.

When scientists are trying to capture an occultation they might use a single telescope that tracks the shadow of the object’s passage, or up to 100 telescopes strategically distributed to map out the shape of an object and discover or characterise satellites and asteroids. These telescopes need to be smaller and more mobile than their more static, larger equivalents used for other research.

Setting up the telescope and commissioning it was a major operation that required state-of-the-art facilities and human power. Students and staff from UWC’s Physics & Astronomy department worked hard to prepare for the observation, learning about telescope operations and the required software.

Some modification was also required. The telescope arrived from the factory with a faulty GPS that was replaced and a little too short for our purposes. We used 3D printing technology in the university’s Modern African Nuclear Detector Laboratory to rectify the length and match the telescope focal point.

Then it was time for the main event.

Capturing the moment

On 4 August 2024, my UWC colleague Siyambonga Matshawule, together with two of my postdocs, Cebo Ngwetsheni and Craig Mehl, and my PhD student Elijah Akakpo travelled to the viewing spot. They joined professors Michael Skrutskie and Anne Verbiscer from the University of Virginia and NASA, both principal investigators of Pluto’s occultation and other NASA missions such as New Horizons.

The viewing spot was in a remote area in South Africa’s Northern Cape province, about 40km north from the town of Upington. This was precisely the central point or dead centre of Pluto’s shadow on Earth, extending 2,377km in diameter, passing across South Africa and Namibia at 85,000 km/h. Considering that, at the same time, our Earth is also moving at an orbital velocity of 107,000 km/h, nailing just the right timing and position for our telescope was crucial.

Read More: 100 years ago, our understanding of the universe exploded

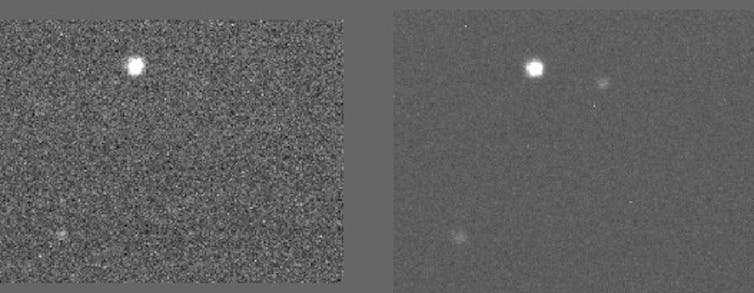

The temperature reached 0°C and the sky above our viewing point was partially cloudy. But the clouds opened up at just the right time and place – and, while the occultation lasted only a few seconds, it may have been enough to get crucial information about Pluto’s atmosphere.

The problem was that a sudden and unexpected wind surge briefly shook the telescope (and our hearts) during the occultation. We’re doing further processing to remove the resulting noise.

Scientific discovery

During the occultation, the starlight starts dimming as it gets absorbed by Pluto’s atmosphere. Shortly after, a central flash occurs right at the dead centre of Pluto’s shadow, where Pluto’s atmosphere acts as a magnifying glass and the star looks brighter than before or after the occultation.

After the central flash the star starts dimming again and eventually returns to its usual brightness. It is that central flash that shows how the starlight refracts through Pluto’s atmosphere and provides crucial information on its temperature and chemical composition. This information is input to atmospheric models that tell us if the atmosphere is finally contracting.

It’s still too soon to unpack any findings about Pluto’s atmosphere from our observation, and it may well be that we can’t see anything quantitative in the data during our first attempt. If not, around the same time next year we’ll get another opportunity. And this time we’ll be well prepared for sudden wind surges. We’ll also bring hot water bottles. Adventure is out there!

- is a Full Professor of Physics, University of the Western Cape

- This article first appeared in The Conversation

1 Comment

Pluto’s demotion is still rejected by most planetary scientists, including New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern and most of the New Horizons team. Stern is the scientist who coined the term “dwarf planet” back in 1991, but he did so to designate a new subclass of planets, not to designate a class of non-planets. Just 4% of the IAU voted on the controversial demotion, and most weren’t planetary scientists but other types of astronomers. An equal number of planetary scientists led by Stern signed a formal petition rejecting the IAU definition, which misused Stern’s term. To this day, most planetary scientists favor the geophysical planet definition, which considers dwarf planets a subclass of planets and does not require objects to clear their orbits to be considered planets. This debate is very much ongoing.