Last week, several major record labels filed copyright infringement lawsuits in US courts against the makers of two generative AI music apps, Suno and Udio. The labels allege the AI companies have engaged in copyright infringement by copying many sound recordings belonging to the record labels, and producing outputs very similar to those recordings.

The labels are seeking damages of US$150,000 (R2,770,185) for each of the thousands of tracks of which copyright has allegedly been infringed.

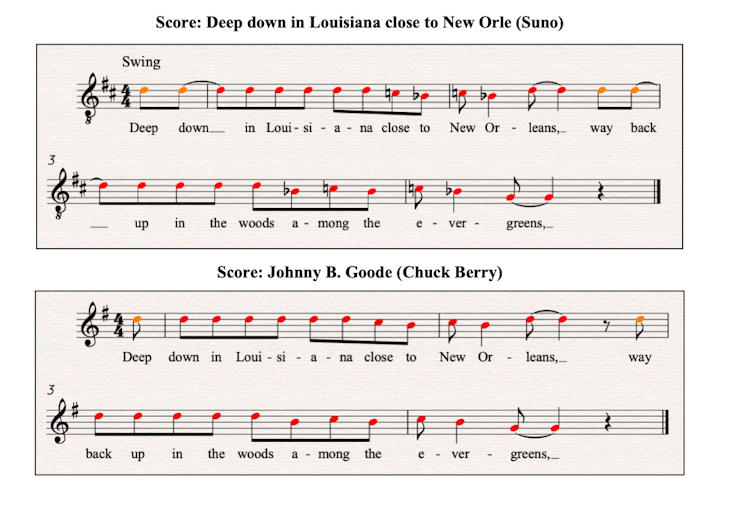

The lawsuits allege Udio produced output with “striking resemblances” to songs including Dancing Queen by ABBA and All I Want For Christmas Is You by Mariah Carey, while Suno allegedly turned out songs similar to I Got You (I Feel Good) by James Brown and Johnny B. Goode by Chuck Berry, among others.

Pretty amazing stuff from the Udio/Suno lawsuits. Record labels were able to basically recreate versions of very famous songs with highly specific prompts, then linked to them in the lawsuits. I made a short compilation here:https://t.co/9Nu7rW7eqD pic.twitter.com/5fQaD0wQ2I

— Jason Koebler (@jason_koebler) June 24, 2024

These lawsuits are not the first to trouble the booming generative AI industry. Visual artists have sued makers of image-generating systems, while various newspapers are suing OpenAI, the owner of ChatGPT, for similar allegations. The result of the litigation may determine the future viability of such generative AI products.

How do music generators work?

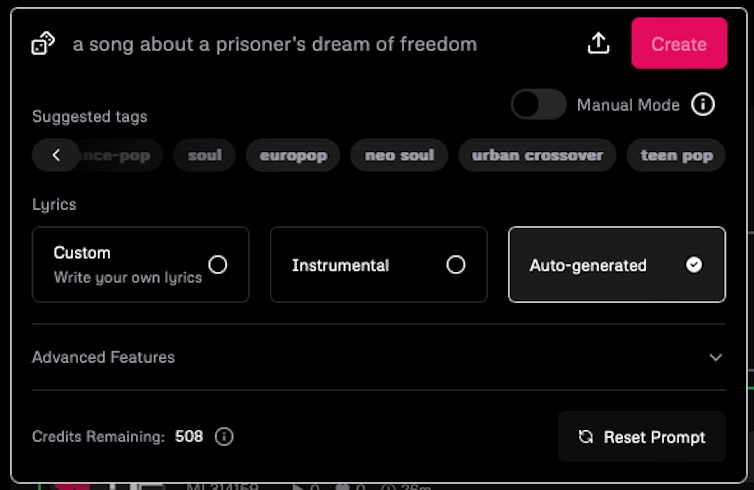

For those who have not used these types of products, they work like this. You type in a text prompt, such as “Compose a female jazz song about beating the Monday morning blues”. If you like, you can also provide your own lyrics.

The app then generates output in the form of an MP3 song, with a combination of vocals and instrumentation, which can be downloaded by the user.

To generate the song, the AI has been trained with a vast amount of data. The lawsuits allege this data comprises pre-existing sound recordings owned by various record labels and copied without permission. These sound recordings are at the heart of this issue.

The litigation is likely to hinge on whether what Suno and Udio have done with any of these sound recordings is found to be “fair use”.

In the US, fair use is a defence to copyright infringement. In Australia, we have a narrower “fair dealing” copyright doctrine which pertains to particular uses such as research and study.

How will the court make its decision?

The court will examine four factors in relation to the use of the record labels’ songs by Suno and Udio. These are:

- the purpose and character of the use

- the nature of the original copyright work

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used, and

- the effect of the use on market value.

The most contentious factor is the purpose and character of the use. This involves examining whether the generative AI music is sufficiently “transformative”, which means it provides a new meaning, expression or value to the original work.

At the heart of Suno and Udio’s argument is that their technology is sufficently transformative in nature. They argue that this is because their AI synthesises new, original output, rather than copying and reproducing pre-existing songs.

The court will examine the amount and substantiality of the portion of songs copied. It will examine how the allegedly copied songs are used in the AI training process and in generating output.

The element of substantiality may be qualitative, rather than quantitative. This means that in addition to the amount copied, the court can also consider whether a distinctive part of a song has been copied.

Read More: No, AI doesn’t mean human-made music is doomed. Here’s why

In addition, the effect of the generative AI use on the market value of the original sound recording will be considered. A use which substitutes for the original song in the market is more likely to be considered substantial. This point can be argued both ways.

What’s in a voice?

One major concern for the music industry is the cloning of voices. This is where other generative AI music apps (not Suno or Udio) can be used to clone a famous singer’s voice onto any song.

Suno released a statement on X, denying that voice cloning is possible using their app, because it does not allow users to reference particular singers. This issue will likely be contested in court.

Today, we’d like to share some thoughts on AI and the future of music.

In the past two years, AI has become a powerful tool for creative expression across many media—from text to images to film, and now music.

At Udio, our mission is to empower artists of all kinds to create…

— udio (@udiomusic) June 25, 2024

What will happen next? It is difficult to predict.

Perhaps a settlement will be reached prior to the hearings. Perhaps new licensing arrangements between the parties will be developed, in a similar situation to OpenAI’s recent collaboration with News Corp.

What is certain is that there are other new AI voice cloning innovations being developed through start-up companies, to monetise and license voice cloning. One example is Hooky, a licensing platform for AI voice modelling, which provides artists with control over the use of their voice.

If the record labels’ litigation proceeds, it will give American courts the opportunity to clarify whether training activities and output from generative AI music apps are captured under fair use. This decision may also set a precedent for the activities conducted by other types of generative AI apps.

- is a Lecturer in Law, University of New England

- This article first appeared in The Conversation