Astronomers have been working to better understand the galactic environments of fast radio bursts (FRBs) – intense, momentary bursts of energy occurring in mere milliseconds and with unknown cosmic origins.

Now, a study of the slow-moving, star-forming gas in the same galaxy found to host an FRB has been published in The Astrophysical Journal. This is only the fourth-ever publication on two completely different areas of astronomy describing the same galaxy.

Even more remarkable is the fact that a single telescope made the discovery possible – from the same observation.

Fast radio mysteries

FRBs, first detected in 2007, are incredibly powerful pulses of radio waves. They originate from distant galaxies, and the signal typically only lasts a few milliseconds

FRBs are immensely useful for studying the cosmos, from investigating the matter that makes up the universe, to even using them to constrain the Hubble constant – the measure of how much the universe is expanding.

However, the origin of FRBs is an ongoing puzzle for astronomers. Some FRBs are known to repeat, sometimes over a thousand times. Others have only been detected once.

Whether these repeating or non-repeating signals have formed differently is currently being investigated by several research groups. At one point, we had more theories on how fast radio bursts are made than detections of them.

It’s an exciting time to be studying FRBs, as showcased by the recent study associating an FRB with a gravitational wave. If that finding holds true, it means at least some FRBs could be created by two neutron stars merging to form a black hole.

However, it is hard to pinpoint where exactly fast radio bursts come from. They are extremely bright yet so brief, getting an accurate position is hard for many radio telescopes. Without knowing where precisely these bursts originate, we cannot study the galaxies they are found in. And without knowing the environments FRBs are formed in, we cannot fully solve their mysteries.

One telescope in Australia is now helping us figure it out.

The tool for the job

CSIRO’s ASKAP radio telescope (Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder), located in the Western Australian desert, is a remarkable instrument. Made up of an array of 36 dishes separated by up to six kilometres, ASKAP can detect FRBs and pinpoint them to their host galaxies.

ASKAP can in fact perform its FRB search at the same time as observations for other science surveys. One such ASKAP survey will map the star-forming gas in galaxies across the Southern sky, helping us understand how galaxies evolve.

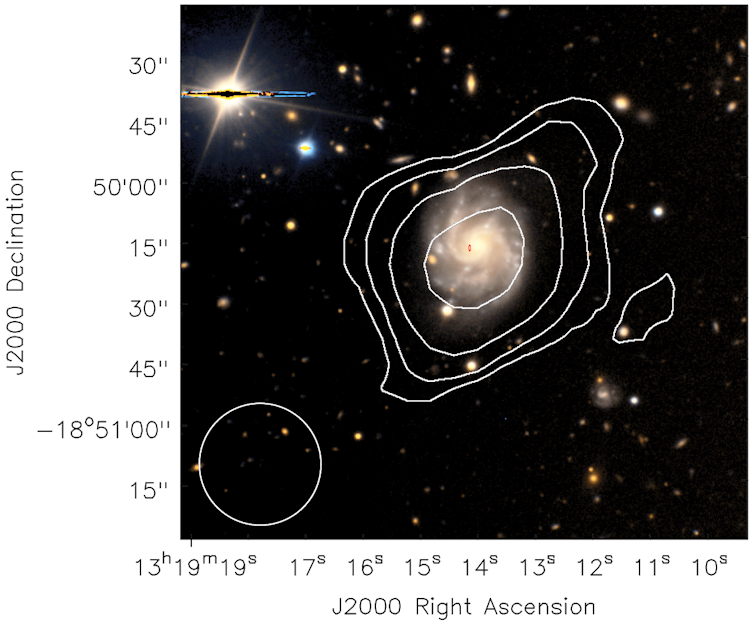

During a recent observation for this survey, ASKAP also detected a new FRB, and we were able to identify the galaxy it comes from – a nearby spiral galaxy much like our own Milky Way.

A gas-filled galaxy

ASKAP was able to find the cold neutral hydrogen gas – the source of star formation – in this spiral galaxy. As far as FRB host galaxies go, this is already a rare detection of this gas; only three other cases have been published so far. These had required follow-up observations, or relied on other older observations, made with different telescopes.

Here, ASKAP gave us both the FRB and the gas surrounding it. It is the first simultaneous detection of these rarely overlapping occurrences.

Disturbed gas which ASKAP can detect can give us an indication that a galaxy merger recently happened, which tells us about the star forming history of the galaxy. In turn this gives us clues as to what may cause FRBs.

The previous studies of the gas surrounding FRBs found fast radio bursts reside in very dynamic systems, suggesting tumultuous galaxy mergers triggered the bursts.

Read More: The SuperBIT balloon-telescope has just sent back its first images of space

For this particular FRB, however, the host galaxy environment is surprisingly calmer. Further studies will be needed to find out if overall we see disturbed gas environments for FRBs, or if there are distinct scenarios – and potentially multiple creation paths – for FRBs.

More to come

Given the uniqueness of such dual detections, this result showcases the strength and versatility of ASKAP. This is the first simultaneous detection of both an FRB and the gas in its host galaxy.

And this is just the start. ASKAP is set to detect and localise over a hundred FRBs a year. By continuing to work collaboratively with each other, different survey groups will be able to untangle the mysteries behind FRBs, how they form, and their host galaxy environments.

- is a Research Associate, Curtin University

- This article first appeared on The Conversation