The rise in the use of smartphones and an increased adoption of mobile internet in Africa are fundamentally altering the media ecology for election campaigns.

As mobile phones become commonplace, even in Africa’s poorest countries, the uptake of social media has become ubiquitous. Applications like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, WhatsApp and blogs form an integral part of today’s political communication landscape in much of the continent.

These platforms are becoming a dominant factor in electoral processes, playing a tremendous role in the creation, dissemination and consumption of political content.

Their influence and embedded power over political content invites further scrutiny, which informed my research. Is the rise in social media uptake in the continent a game changer in political communications? And if it is, does social media influence political campaigns?

To answer these questions, I considered the interplay between elements in the infrastructure of social media and human agency.

The infrastructure refers to the architecture that makes up social media systems. Even though the infrastructure is not immediately visible, it plays a critical role in the (re)production and dissemination of information.

Human agency entails the choices human beings make when they interact with social media systems.

I found that there are three main ways that political campaigns are influenced via social media: through algorithms, bots and the people who use them.

The power of algorithms

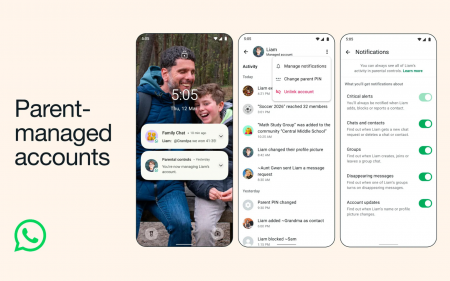

Imbued in social media platforms, with the exception of WhatsApp, is a system of software, codes and algorithms that manage, interpret and disseminate large quantities of information across social media networks.

The power of the algorithm is in its ability to search, sort, rank, prioritise and recommend the content consumed by users. The system, therefore, influences the choices we make.

Algorithms watch your behaviour when you interact with certain content in the platform, make assumptions and predictions on your preferences, and then recommend similar content in your feed.

For instance, if you constantly interact with posts – by liking, replying or sharing – from certain individuals, you are likely to see more posts from them. If you have shown interest in watching videos from a political outfit, you are likely to get more videos from them.

Which items are promoted and why? We may never know why the algorithms are coded (by programmers) in such a way as to rank certain items, individuals or political parties higher. What we know is that these algorithms influence what people see or don’t see.

They have the power to amplify and marginalise certain content and, like human gatekeepers in traditional mass media, determine what information users are exposed to.

For example, Facebook’s EdgeRank algorithm determines what is shown on a user’s Top News by displaying only a subset of stories by one’s friends. These are derived from a set of factors, such as the type of content (links, videos or photos) and the frequency and types of interactions with these friends (like tags or comments).

Similarly, Twitter algorithms display ranked tweets. That is, first they rank them and then display what they think is most relevant to the user.

These algorithms are not neutral. They encode political choices, influencing the information seen by users. When a user opens his or her social media account, he or she will be met by algorithm-filtered and recommended content, based on prior activities and interactions on the platform.

People are then likely to share visible information on non-algorithm-based applications like WhatsApp and Messenger, as well as in mainstream media.

Bots and deepfakes

Social bots can also be deployed to manipulate public opinion and influence votes. They mimic and potentially manipulate humans and their behaviour on social networks. They run automatically to produce messages, post online and interact with users through likes, comments and follows (fake accounts).

Even more worrisome is the rise of deepfakes. This involves the use of artificial intelligence to fabricate images and videos by replacing the face or voice of someone, usually a public figure, with someone else’s in a way that makes the content look authentic.

The intention is often to mislead the audience and make them believe that the targeted public figure said something (often controversial or provocative).

As noted by Portland Communications, a strategic communications consultancy, in their report, How Africa Tweets, Twitter bots account for more than 20% of influencers in countries like Lesotho and Kenya.

One of the surprising findings in the report was the limited influence of politicians on the conversation.

Human element

African political parties are spending huge sums hiring consultancy companies with expertise in digital campaigning and even manipulation of social media content.

International consultancy firms like the now defunct Cambridge Analytica (CA) have been accused of attempting to influence digital campaigns in Africa and in other parts of the world. CA worked on several campaigns in Russia, the UK, USA and Kenya.

In Kenya, it emerged that President Uhuru Kenyatta had hired CA ahead of the 2013 elections. CA’s activities sparked global outcry when it became known, culminating in its collapse.

It is evident that those with political power and money can easily hire automated systems, like bots, to influence the flow of political content across social media. They can also distort information.

The role of non-human actors should be worrying to anyone keen on democratic processes.

There are indications that social media algorithms and bots are slowly changing the dynamics of elections in Africa. This is seen in the number of political parties hiring a new breed of communicators, such as social media managers.

The interplay between media and politics is central to any understanding of political campaigns, given their role as conduits of political information, persuasion and discussion. Social media provides spaces for participation – but also for misinformation and disinformation.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.