In early 2022, nearly two years after Covid was declared a pandemic by the World Health Organization, experts are mulling a big question: when is a pandemic “over”?

So, what’s the answer? What criteria should be used to determine the “end” of Covid’s pandemic phase? These are deceptively simple questions and there are no easy answers.

I am a computer scientist who investigates the development of ontologies. In computing, ontologies are a means to formally structure knowledge of a subject domain, with its entities, relations and constraints, so that a computer can process it in various applications and help humans to be more precise.

Ontologies can discover knowledge that’s been overlooked until now: in one instance, an ontology identified two additional functional domains in phosphatases (a group of enzymes) and a novel domain architecture of a part of the enzyme. Ontologies also underlie Google’s Knowledge Graph that’s behind those knowledge panels on the right-hand side of a search result.

Applying ontologies to the questions I posed at the start is useful. This approach helps to clarify why it is difficult to specify a cut-off point at which a pandemic can be declared “over”. The process involves collecting definitions and characterisations from domain experts, like epidemiologists and infectious disease scientists, consulting relevant research and other ontologies and investigating the nature of what entity “X” is.

“X”, here, would be the pandemic itself – not a mere shorthand definition, but looking into the properties of that entity. Such a precise characterisation of the “X” will also reveal when an entity is “not an X”. For instance, if X = house, a property of houses is that they all must have a roof; if some object doesn’t have a roof, it definitely isn’t a house.

With those characteristics in hand, a precise, formal specification can be formulated, aided by additional methods and tools. From that, the what or when of “X” – the pandemic is over or it is not – would logically follow. If it doesn’t, at least it will be possible to explain why things are not that straightforward.

This sort of precision complements health experts’ efforts, helping humans to be more precise and communicate more precisely. It forces us to make implicit assumptions explicit and clarifies where disagreements may be.

Definitions and diagrams

I conducted an ontological analysis of “pandemic”. First, I needed to find definitions of a pandemic.

Informally, an epidemic is an occurrence during which there are multiple instances of an infectious disease in organisms, for a limited duration of time, that affects a community of said organisms living in some region. A pandemic, as a minimum, extends the region where the infections take place.

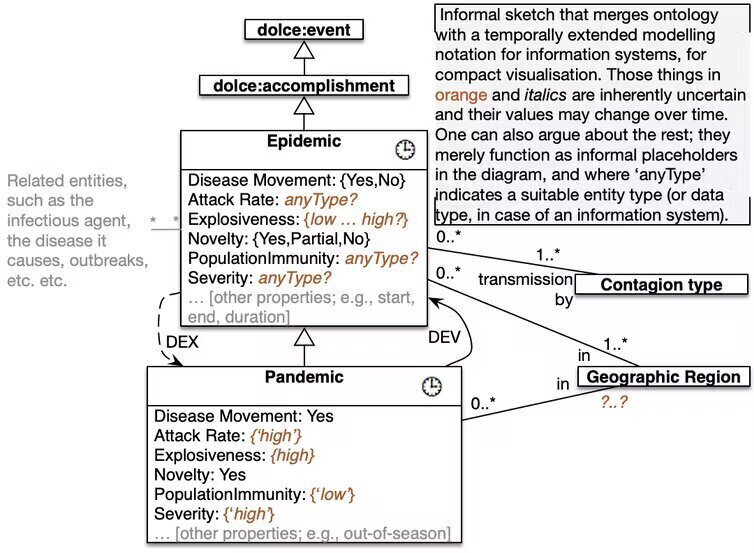

Next, I drew from an existing foundational ontologies. This contains generic categories like “object”, “process”, and “quality”. I also used domain ontologies, which contain entities specific to a subject domain, like infectious diseases. Among other resources, I consulted the Infectious Disease Ontology and the Descriptive Ontology for Linguistic and Cognitive Engineering.

First, I aligned “pandemic” to a foundational ontology, using a decision diagram to simplify the process. This helped to work out what kind of thing and generic category “pandemic” is:

(1) Is [pandemic] something that is happening or occurring? Yes (perdurant, i.e., something that unfolds in time, rather than be wholly present).

(2) Are you able to be present or participate in [a pandemic]? Yes (event).

(3) Is [a pandemic] atomic, i.e., has no subdivisions and has a definite end point? No (accomplishment).

The word “accomplishment” may seem strange here. But, in this context, it makes clear that a pandemic is a temporal entity with a limited lifespan and will evolve – that is, cease to be a pandemic and evolve back to epidemic, as indicated in this diagram.

Characteristics

Next, I examined a pandemic’s characteristics described in the literature. A comprehensive list is described in a paper by US infectious disease specialists published in 2009 during the global H1N1 influenza virus outbreak. They collated eight characteristics of a pandemic.

Read more: New COVID data: South Africa has arrived at the recovery stage of the pandemic

I listed them and assessed them from an ontological perspective:

- Wide geographic extension. This is an imprecise feature – be it fuzzy in the mathematical sense or estimated by other means: there isn’t a crisp threshold when “wide” starts or ends.

- Disease movement: there’s transmission from place to place and that can be traced. A yes/no characteristic, but it could be made categorical or with ranges of how slowly or fast it moves.

- High attack rates and explosiveness, or: many people are affected in a short timespan. Many, short, fast – all indicate imprecision.

- Minimal population immunity: immunity is relative. You have it to a degree to some or all of the variants of the infectious agent, and likewise for the population. This is an inherently fuzzy feature.

- Novelty: A yes/no feature, but one could add “partial”.

- Infectiousness: it must be infectious (excluding non-infectious things, like obesity), so a clear yes/no.

- Contagiousness: this may be from person to person or through some other medium. This property includes human-to-human, human-animal intermediary (e.g., fleas, rats), and human-environment (notably: water, as with cholera), and their attendant aspects.

- Severity: Historically, the term “pandemic” has been applied more often for severe diseases or those with high fatality rates (e.g., HIV/AIDS) than for milder ones. This has some subjectivity, and thus may be fuzzy.

Properties with imprecise boundaries annoy epidemiologists because they may lead to different outcomes of their prediction models. But from my ontologist’s viewpoint, we’re getting somewhere with these properties. From the computational side, automated reasoning with fuzzy features is possible.

COVID, at least early in 2020, easily ticked all eight boxes. A suitably automated reasoner would have classified that situation as a pandemic. But now, in early 2022? Severity (point 8) has largely decreased and immunity (point 4) has risen. Point 5 – are there worse variants of concern to come – is the million-dollar question. More ontological analysis is needed.

Highlighting the difficulties

Ontologically speaking, then, a pandemic is an event (“accomplishment”) that unfolds in time. To be classified as a pandemic, there are a number of features that aren’t all crisp and for which the imprecise boundaries haven’t all been set. Conversely, it implies that classifying the event as “not a pandemic” is just as imprecise.

This isn’t a full answer as to what a pandemic is ontologically, but it does shed light on the difficulties of calling it “over” – and illustrates well that there will be disagreement about it.

This article first appeared on The Conversation.