On Feb. 22, 2022, AT&T is scheduled to turn off its 3G cellular network. T-Mobile is scheduled to turn its off on July 1, 2022, and Verizon is slated to follow suit on Dec. 31, 2022.

The vast majority of cellphones in service operate on 4G/LTE networks, and the world has begun the transition to 5G, but as many as 10 million phones in the U.S. still rely on 3G service. In addition, the cellular network functions of some older devices like Kindles, iPads and Chromebooks are tied to 3G networks. Similarly, some older internet-connected systems like home security, car navigation and entertainment systems, and solar panel modems are 3G-specific. Consumers will need to upgrade or replace these systems.

So why are the telecommunications carriers turning off their 3G networks? As an electrical engineer who studies wireless communications, I can explain. The answer begins with the difference between 3G and later technologies such as 4G/LTE and 5G.

Picture a family trip. Your spouse is on the phone arranging activities to do at the destination, your teenage daughter is streaming music and chatting with her friends on her phone, and her younger sibling is playing an online game with his friends. All those separate conversations and data streams are communicated over the cellular network, seemingly simultaneously. You probably take this for granted, but have you ever wondered how the cellular system can handle all those activities at the same time, from the same car?

Communicating all those messages

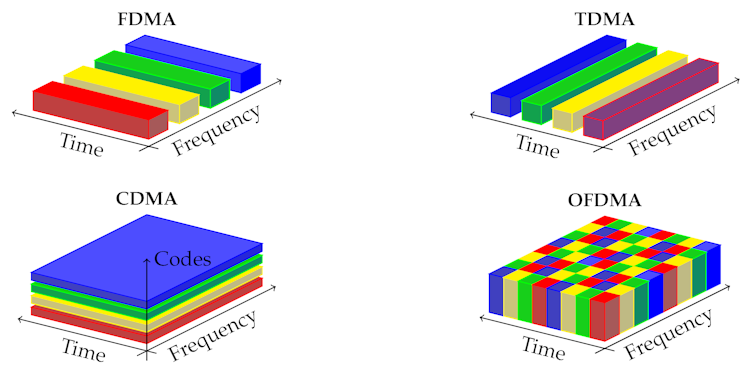

The answer is a technological trick called multiple access. Imagine using a sheet of paper to write messages to 100 different friends, one private message for each person. The multiple access technology used in 3G networks is like writing every message to each of your friends using the whole sheet of paper, so all the messages are written on top of each other. But you have a special set of pens with different colors that allows you to write each message in a unique color, and each of your friends has a special pair of glasses that reveals only the color intended for that person.

However, the number of colored pens is fixed, so if you want to send messages to more people than the number of colored pens you have, you will need to start mixing colors. Now when a friend applies their special lenses, they will see a little bit of the messages to other friends. They won’t see enough to read the other messages, but the overlap might be enough to blur the message intended for them, making it harder to read.

The multiple access technology used by 3G networks is called Code Division Multiple Access, or CDMA. It was invented by Qualcomm founder Irwin M. Jacobs with several other prominent electrical engineers. The technique is based on the concept of spread spectrum, an idea that can be traced back to the early 20th century. Jacobs’ 1991 paper showed that CDMA can increase the cellular capacity manyfold over systems at the time.

CDMA lets all cellular users send and receive their signals at all times and over all frequencies. So if 100 users wish to initiate a call or use a cell service at around the same time, their 100 signals will overlap with each other over the entire cellular spectrum for the whole time they communicate.

The overlapping signals create interference. CDMA solves the interference problem by letting each user have a unique signature: a code sequence that can be used to recover each user’s signal. The code corresponds to the color in our paper analogy. If there are too many users on the system at the same time, the codes can overlap. This leads to interference, which gets worse as the number of users increases.

Slices of time and spectrum

Instead of allowing users to share the entire cellular spectrum at all times, other multiple access techniques divide access by time or frequency. Division over time creates time slots. Each connection can last over multiple time slots spread out in time, but each time slot is so short – a matter of milliseconds – that the cellphone user doesn’t perceive the interruptions from alternating time slots. The connection appears to be continuous. This time slicing technique is time-division multiple access (TDMA).

The division can also be done in frequency. Each connection is given its own frequency band within the cellular spectrum, and the connection is continuous for its duration. This frequency slicing technique is frequency division multiple access (FDMA).

In our paper analogy, FDMA and TDMA are like dividing the paper into 100 strips in either dimension and writing each private message on one strip. FDMA would be, for example, horizontal strips, and TDMA would be vertical strips. With individual strips, all messages are separated.

4G/LTE and 5G networks use Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiple Access (OFDMA), a highly efficient combination of FDMA and TDMA. In the paper analogy, OFDMA is like drawing strips along both dimensions, dividing the whole paper into many squares, and assigning each user a different set of squares according to their data need.

End of the line for 3G

Now you have a basic understanding of the difference between 3G and the later 4G/LTE and 5G. You might still reasonably ask why 3G needs to be shut down. It turns out that because of those differences in the access technology, the two networks are built using completely different equipment and algorithms.

3G handsets and base stations operate on a wideband system, meaning they use the whole cellular spectrum. 4G/LTE and 5G operate on narrowband or multi-carrier systems, which use slices of the spectrum. These two systems need completely different sets of hardware, from the antenna on the cell tower down to the components in your phone.

So if your phone is a 3G phone, it cannot connect to a 4G/LTE or 5G tower. For a long while, the cellular service providers have been keeping their 3G networks going while building a completely separate network with new tower equipment and servicing new handsets using 4G/LTE and 5G. Imagine bearing the cost of operating two separate networks at the same time for the same purpose. Eventually, one has to go. And now, as the carriers are starting to deploy 5G systems in earnest, that time has come for 3G.

This article first appeared on The Conversation