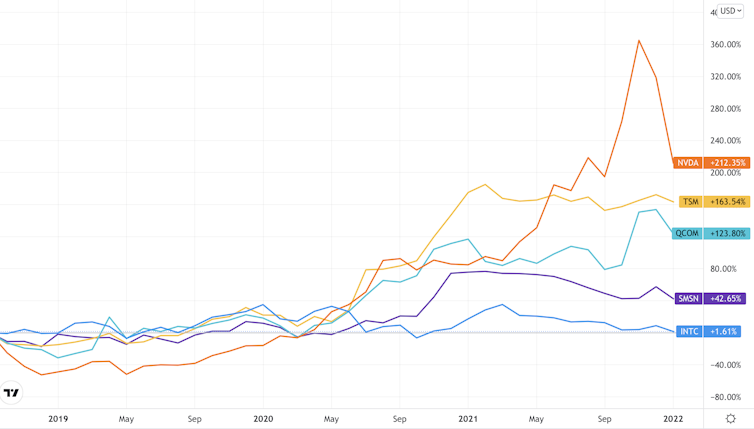

American chip-making giant Intel is a shadow of its former self. Despite the global semiconductor shortage, which has boosted rival chipmakers, Intel is making less money than a year ago with net income down 21% year over year to US$4.6 billion (£3.4 billion). Unfortunately, this is an ongoing trend.

Intel was the world’s largest chipmaker until 2021, when it was dethroned by Samsung. Though Samsung’s main business is memory chips, which is a different segment of the market to Intel’s microprocessors, it is sign of Intel’s decline. We’ve been tracking global companies’ future-readiness at the International Institute for Management Development (IMD), and Intel now comes out 16th in the technology sector.

There are two fundamental issues, according to Matt Bryson, an analyst at Wedbush Securities: “[Intel] fell behind AMD in chip design and Taiwan Semiconductor (TSMC) in manufacturing.” During the most recent earnings call with analysts, CEO Pat Gelsinger had to concede that the technology in Intel’s data-centre processors hadn’t been improved in five years. In his words, it was “an embarrassing thing to say”.

How did this happen to a company that for many years was well ahead of its competition, and what are the chances of a turnaround?

Intel’s in-house model

Intel used to be the undisputed king of microprocessors. PCs were made by many companies, but these were effectively just brand names. The prowess of the machines depended on whether they had an “Intel inside”.

Here is how you compete as a chipset manufacturer: you etch more transistors on a slice of silicon wafer. To achieve this, Intel outspent its rivals on R&D and attracted the best scientists. But most importantly, it kept full control of both product design and manufacturing.

Intel’s engineers – from research to design to manufacturing – have always worked as a close in-house team. In contrast, fellow US rivals like Qualcomm, Nvidia and AMD, have either shed their manufacturing capacity or never had it in the first place. They outsource to suppliers such as TSMC and other third-party foundries for the same reason that most of the stuff sold in Walmart is made in China: it’s cheaper.

Share performances of leading chipmakers, 2019-22

The challenge with outsourcing manufacturing is that your suppliers are probably not in the same building as you. Meetings won’t happen at the watercoolers or in the staff cafeteria. It takes scheduling and coordination. There’s bureaucracy. It’s hard to be on the same page.

The problems that this can cause can be all too evident – for a long while, TSMC and Nvidia would be blaming each other for manufacturing issues, for instance. For years, Intel’s one-team approach enabled it to pull further and further away from the competition, with processors that were the most powerful. Yet what happened next was the classic disruption.

The great library of Taiwan

When mobile took off, the chipset didn’t require as much computing power as those in a laptop or PC, since the priority was energy-saving to extend battery life on a single charge. As Intel was in the business of selling top-quality chips for high margins, it left its rivals to supply chipsets for this new market. As a result, Intel got locked into selling ever more expensive and power-guzzling CPUs for PCs.

With Qualcomm and Apple increasing orders to TSMC to supply Androids and iPhones, the Taiwanese supplier had to master remote work many years before the rest of us. It built up a formidable intellectual property (IP) library online, containing not only its own IP but also that of other suppliers in the value chain.

TSMC could now quickly tell its customers what was possible from a manufacturing perspective and encode such knowledge into design rules. Transparency was total. Its customers could take what was available from the menu and stretch their product design to the limit.

TSMC’s library has gradually become the industry’s largest. The best part is that workflow coordination is done online in a “virtual foundry” system that involves performance simulation, computer modelling and instant feedback. With virtual workflow that improves month after month, year after year, TSMC has steadily neutralised Intel’s advantages.

Risk and demand

TSMC doesn’t have to shoulder the risks of launching a new product. It just needs to excel in manufacturing, because if a Qualcomm product fails, AMD’s may take off. TSMC can switch capacity from one client to another. Risk is mitigated when demand is pooled.

For chip designers, outsourcing to TSMC has gradually meant they can afford to be fast-moving and bold in product design. If a new chip doesn’t sell, they can pull the plug without having to worry about the factory: that’s TSMC’s problem.

That’s how Nvidia has evolved beyond deploying graphic processors only in the gaming sector; it’s now leading in designing chipsets for AI applications. And AMD, an underdog close to bankruptcy in 2014, now makes some of the most powerful processors.

Intel, meanwhile, still needs to ensure that every product wins with enough volume to feed its network of factories, each costing billions of dollars. This has made the company more and more conservative. And having stuck to supplying chips to PCs, servers and data centres, it is struggling to innovate. Tellingly, the company’s gross margin – total revenue minus the cost of production – has been sliding for nearly a decade. The biggest danger for a technology company is that it’s not developing leading-edge products fast enough, backsliding into selling commodities.

The big issue for Pat Gelsinger is, how can a company built on self-reliance transform its culture quickly? He is talking about building a foundry service to regain scale in manufacturing. But the question is, how can Intel become a collaborative organisation not in a decade, but in a year?

Andy Grove, the legendary late chairman of Intel got it right. He said: “Only the paranoid survive.”

- is a Professor of Management and Innovation, International Institute for Management Development (IMD)

- This article first appeared in The Conversation