On paper, privacy rights for citizens of countries throughout Africa are well protected. Privacy rights are written into constitutions, international human rights conventions and domestic law.

But, in the first comparative review of privacy protections across Africa, the evidence is clear: governments are purposefully using laws that lack clarity. Or they ignore laws completely in order to carry out illegal digital surveillance of their citizens.

What’s more, they are doing so with impunity.

This matters because people’s lives are increasingly being lived online, through conversations on social media, online banking and the like.

We’ve just published research on privacy protections in six African countries – Egypt, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Sudan. And the evidence is clear: governments are using laws that lack clarity, or ignoring laws completely, to carry out illegal surveillance of their citizens.

Those targeted include political opponents, business rivals and peaceful activists. In many cases they were conducting mass surveillance of citizens.

Our report finds that existing surveillance law is being eroded by six factors:

- the introduction of new laws that expand state surveillance powers

- lack of legal precision and privacy safeguards in existing surveillance legislation

- increased supply of new surveillance technologies that enable illegitimate surveillance

- state agencies regularly conducting surveillance outside of what is permitted in law

- impunity for those committing illegitimate acts of surveillance

- insufficient capacity in civil society to hold the state fully accountable in law.

Governments argue that it is occasionally necessary to violate the privacy rights of a citizen in order to prevent a much greater crime. For instance, a person may be a suspected terrorist.

But the covert nature of surveillance, and the large power imbalance between the state and the people being watched, presents a clear opportunity to abuse power.

Robust surveillance laws are key to preventing this. They must define exactly when it is legal to conduct narrowly targeted surveillance of the most serious criminals, while protecting the privacy rights of the rest of the population.

African Digital Rights Network

We are a team of researchers from the Institute of Development Studies and the African Digital Rights Network.

We assessed surveillance laws in the six countries using principles from globally accepted human rights frameworks. These included International Principles on the Application of Human Rights to Communications Surveillance, the UN Draft Instrument on Government-led Surveillance and Privacy and the African Commission’s Declaration of Principles of Freedom of Expression and Access to Information.

Our team of researchers produced six country reports that detailed specific cases. These included rulings from the constitutional courts in South Africa and Kenya.

We found that all six countries had conducted surveillance that violated citizens’ constitutional rights. There were many examples of surveillance violating rights or laws. There were no examples of those responsible being charged, subject to legal sanctions, resigning or being fired.

Where the problems lie

To understand whether privacy rights are being violated, it’s necessary to monitor the legality of surveillance. But this is hard to do due to weak legal provisions, and a lack of transparency and oversight.

Monitoring surveillance practice against privacy right protections requires well defined transparency and independent oversight mechanisms. These are entirely missing or deficient in all of the countries studied. With the exception of South Africa, countries studied lacked a single law clearly defining legal surveillance and privacy safeguards.

In addition, piecemeal provisions, spread across multiple pieces of legislation, can conflict with each other. This makes it impossible for citizens to know what law is applicable.

We found a number of barriers to making surveillance more accountable.

- Legal provisions enabling surveillance are found in different laws. This makes it difficult to tell which law applies.

- Independent oversight bodies to monitor the activities of law enforcement authorities are absent.

- Investigating authorities do not publicly report on their activities.

- Individuals subject surveillance are not notified about it nor are they afforded the opportunity to appeal.

- There are several surveillance provisions that are not subject to the supervision of a judge. For instance, access to a database of subscribers by security agencies only requires the approval of a government agency (such as the Nigeria Communication Commission) which is granted under the Registration of Telephone Subscribers Regulations.

Beyond the use (or abuse) of law we also found evidence of states investing in new surveillance technologies. These included artificial intelligence-based internet and mobile surveillance, mobile spyware, biometric digital ID systems, CCTV with facial recognition and vehicle licence plate recognition.

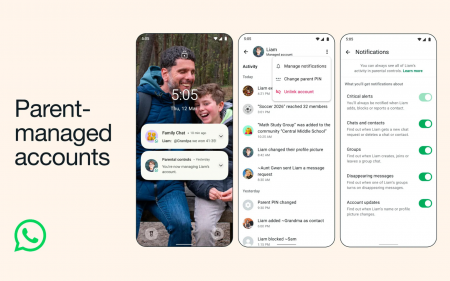

In Nigeria, for example, the government increased spending in the last decade on acquiring various surveillance technologies. More recently it approved a supplementary budget to purchase tools capable of monitoring encrypted WhatsApp communications.

This combination of new technologies and surveillance law breaches points to an urgent need to strengthen existing laws by applying human rights principles.

How to close the gaps

We recommend that an independent oversight body should supervise the activities of the investigating authorities. We also recommend the use of strategic litigation to challenge existing laws and actions that violate constitutionally guaranteed rights.

Alongside improving the law must be action to raise public awareness of privacy rights and surveillance practices. A strong civil society, independent media and independent courts are needed to challenge government actions. This is critical for holding governments accountable and upholding the privacy rights of citizens everywhere.

Abrar Mohamed Ali, Mohamed Farahat, Ridwan Oloyede and Grace Mutung’u were the researchers on this project. Ridwan Oloyede assisted in the writing of this article.

- is a Digital Research Fellow, Institute of Development Studies

- This article first appeared on The Conversation