How many emails are in your inbox? If the answer is thousands, or if you often struggle to find a file on your computer among its cluttered hard drive, then you might be classed as a digital hoarder.

In the physical world, hoarding disorder has been recognised as a distinct psychiatric condition among people who accumulate excessive amounts of objects to the point that it prevents them living a normal life. Now, research has begun to recognise that hoarding can be a problem in the digital world, too.

A case study published in the British Medical Journal in 2015 described a 47-year-old man who, as well as hoarding physical objects, took around 1,000 digital photographs every day. He would then spend many hours editing, categorising, and copying the pictures onto various external hard drives. He was autistic, and may have been a collector rather than a hoarder — but his digital OCD tendencies caused him much distress and anxiety.

The authors of this research paper defined digital hoarding as “the accumulation of digital files to the point of loss of perspective which eventually results in stress and disorganisation”. By surveying hundreds of people, my colleagues and I found that digital hoarding is common in the workplace. In a follow-up study, in which we interviewed employees in two large organisations who exhibited lots of digital hoarding behaviours, we identified four types of digital hoarder.

“Collectors” are organised, systematic and in control of their data. “Accidental hoarders” are disorganised, don’t know what they have, and don’t have control over it. The “hoarder by instruction” keeps data on behalf of their company (even when they could delete much of it). Finally, “anxious hoarders” have strong emotional ties to their data — and are worried about deleting it.

Working life

Although digital hoarding doesn’t interfere with personal living space, it can clearly have a negative impact upon daily life. Research also suggests digital hoarding poses a serious problem to businesses and other organisations, and even has a negative impact on the environment.

To assess the extent of digital hoarding, we initially surveyed more than 400 people, many of whom admitted to hoarding behaviour. Some people reported that they kept many thousands of emails in inboxes and archived folders and never deleted their messages. This was especially true of work emails, which were seen as potentially useful as evidence of work undertaken, a reminder of outstanding tasks, or were simply kept “just in case”.

Interestingly, when asked to consider the potentially damaging consequences of not deleting digital information – such as the cybersecurity threat to confidential business information – people were clearly aware of the risks. Yet the respondents still showed a great reluctance to hit the delete button.

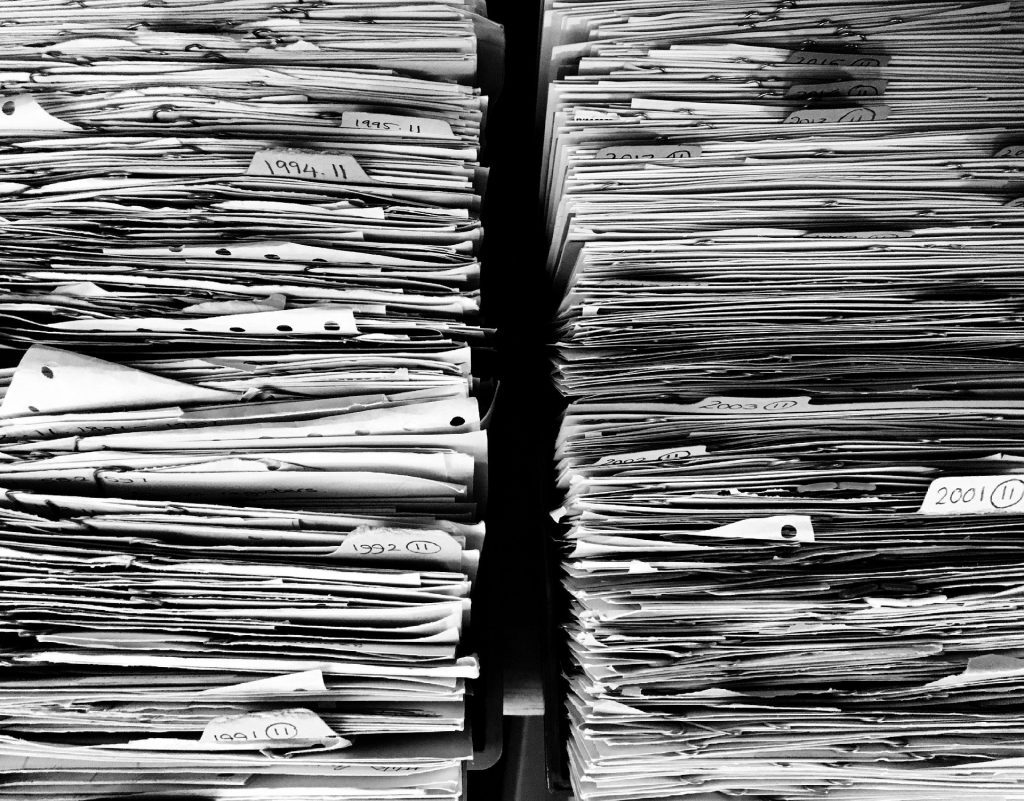

At first glance, digital hoarding may not appear much of a problem — especially if digital hoarders work for large organisations. Storage is cheap and effectively limitless thanks to internet “cloud” storage systems. But digital hoarding may still lead to negative consequences.

First, storing thousands of files or emails is inefficient. Wasting large amounts of time looking for the right file can reduce productivity. Second, the more data is kept, the greater the risk that a cyberattack could lead to the loss or theft of information covered by data protection legislation. In the EU, new GDPR rules mean companies that lose customer data to hacking could be hit with hefty fines.

The final consequence of digital hoarding — in the home or at work — is an environmental one. Hoarded data has to be stored somewhere. The reluctance to have a digital clear-out can contribute to the development of increasingly large servers that use considerable amounts of energy to cool and maintain them.

How to tackle digital hoarding

Research has shown that physical hoarders can develop strategies to reduce their accumulation behaviours. While people can be helped to stop accumulating, they are more resistant when it comes to actually getting rid of their cherished possessions — perhaps because they “anthropomorphise” them, treating inanimate objects as if they had thoughts and feelings.

We don’t yet know enough about digital hoarding to see whether similar difficulties apply, or whether existing coping strategies will work in the digital world, too. But we have found that asking people how many files they think they have often surprises and alarms them, forcing them to reflect on their digital accumulation and storing behaviours.

As hoarding is often associated with anxiety and insecurity, addressing the source of these negative emotions may alleviate hoarding behaviours. Workplaces can do more here, by reducing non-essential email traffic, making it very clear what information should be retained or discarded, and by delivering training on workplace data responsibilities.

In doing so, companies can reduce the anxiety and insecurity related to getting rid of obsolete or unnecessary information, helping workers to avoid the compulsion to obsessively save and store the bulk of their digital data.

- is Associate Professor in Psychology, and Director of the Hoarding Research Group, Northumbria University, Newcastle

- This article first appeared on The Conversation