Sexting — sending sexually suggestive or explicit messages and images — is now a widespread practice, and can be a healthy way to express and explore sexuality. However, there is a need to distinguish between consensual sexting and forms of sexual harassment like cyberflashing.

Cyberflashing refers to the act of non-consensually sending sexual imagery (like nudes or “dick pics”) to another person. It is facilitated through communications technologies including text, AirDrop and social media applications like Snapchat and Tinder.

Similar to flashing — when a person unexpectedly and deliberately “flashes” their genitals to others — that occurs in person, cyberflashing involves an intrusive denial of autonomy and control. It can lead to people feeling distressed, objectified and unsafe.

And like flashing, which involves physical proximity to the person, cyberflashing can occur through location-specific technology like Apple’s AirDrop. A cyberflasher may also access further information about the recipient online, including their name and location.

Cyberflashing is often normalized and perceived as something to laugh off, but it is a form of gender-based sexual violence that must be taken seriously.

My research on technology-facilitated gender-based violence, including non-consensual sexual deepfakes, highlights the need for legal and societal responses to these emerging challenges.

Gendered targets

In 2018, Statistics Canada found that 11 per cent of women and six per cent of men aged 15 or older were sent unwanted sexually suggestive or explicit images or messages. For young people aged 15 to 24, that increased to 25 per cent of women and 10 per cent of men.

Cyberflashing studies from the United States and the United Kingdom suggest higher rates of cyberflashing, with women still being the most targeted.

While further intersectional data is not available for explicit images, generally women with disabilities, Indigenous women and bisexual women face a high prevalence of online harassment overall.

Cyberflashing can also occur alongside further forms of violence including stalking, sexual harassment and physical threats.

Violating impacts

The impacts of cyberflashing are compounded by contextual factors. In one case, a fire inspector in London, Ont., sent explicit photos to women he worked with. Another factor involves location: for instance, women in Montréal received sexually explicit images while riding the Metro, while British students were cyberflashed during university lectures.

A study of 2,045 women and 298 gay or bisexual men in the United States found that women reported cyberflashing as a predominantly negative experience that left them feeling grossed out, disrespected and violated.

The same study found that, although gay and bisexual men received high rates of cyberflashing, they reported more positive reactions, showing how gender and sexual orientation may impact experiences of violence. It is important to situate this finding in terms of unequal gender dynamics, social expectations that men should appreciate sexual advances and a broader culture wherein incidents of sexual violence against men who have sex with men are minimized.

The result of cyberflashing is women engaging in “safety work,” including restricting or changing their movements and communication. Such emotional and physical labour is time-consuming and can limit women’s participation in everyday life.

Rape culture

Cyberflashing reflects and reinforces rape culture wherein sexual violence is normalized and consent is viewed as unnecessary. There is an assumption in cyberflashing that unsolicited sexual content will be positively received despite the lack of consent.

When heterosexual men were asked what reaction they hoped for from the recipient when cyberflashing, the majority of them said that they were after positive reactions like sexual excitement and attraction. A significant minority of men, however, sought negative reactions like shock, disgust and fear.

This frequent, mistaken belief from heterosexual men that there will be a positive reaction to cyberflashing may be because they are socialized to be sexually aggressive.

Beyond individual cyberflashing, rape culture in society more broadly results in belittling sexual violence and victim-blaming. This is reflected in advising women to simply ignore unwanted images and in the wrongful assumption that the person must have “asked” to be flashed.

Moving towards consent

Canada can address cyberflashing by exploring criminalization, a method already present in England, Wales, Scotland and Singapore.

Criminalization of cyberflashing serves as a deterrent by making it an illegal act with potential consequences. Currently, in Canada, only individuals sending sexual content to youth under 18 may face criminal charges under child luring laws if done with the intent to commit an offence such as sexual exploitation, trafficking and indecent exposure.

However, criminalization is limited, given the lack of cyberflashing reporting. Survivors of sexual violence may also distrust the criminal justice system due to its harmful treatment of survivors, especially survivors who face structural oppressions including anti-Black racism and ableism.

Read More: Cybersecurity researchers spotlight a new ransomware threat – be careful where you upload files

A promising alternative to criminalization is transformative justice, an approach to addressing harm that focuses on healing, community accountability and societal change.

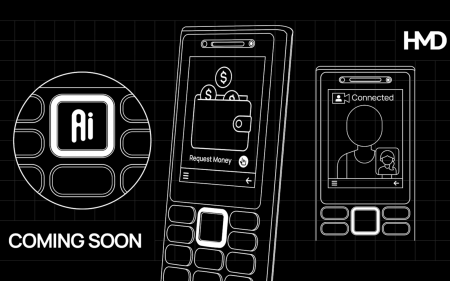

Another aspect of ending cyberflashing requires the participation of social media platforms, which can use technology, including artificial intelligence, to detect sexual content and block it unless the user decides to accept. This approach is used by Bumble’s Private Detector and Instagram’s Nudity Protection.

Finally, there is a need for sex-positive sex and tech safety education that differentiates sexting from sexual harassment like cyberflashing. Rather than stigmatizing sexting overall, age-appropriate practices should be promoted on how to meaningfully and consensually communicate about sex.

- is a PhD Candidate, Political Science, Western University

- This article first appeared in The Conversation