Not surprisingly, Paul McCartney was positive about the appearance this week of what has been trailed as the “last” Beatles song, Now and Then.

Much has been made of AI being part of the production. Machine learning was used to recognise John Lennon’s voice, and then isolate it from other sounds – a piano, a television in the background, electrical hum – to make it usable in a new recording. It also comes amid a slew of Beatles-related activity recently – a new podcast series, Peter Jackson’s epic 2021 documentary Get Back, new versions of the famed Red and Blue compilation albums, and a Paul McCartney tour, during which he is playing some of the Fab Four’s back catalogue.

The commercial juggernaut seems unstoppable, so it’s perhaps easy to be cynical about a “new” song from a band that broke up in 1970, two of whose members are dead. Certainly, Now and Then does raise questions about how technologically mediated releases relate to collective artistic output, and what it means to be a band.

Collective creativity in bands

In many ways, though, the AI label is a red herring, and this new song – which actually has its roots in a John Lennon demo tape from 1977 – demonstrates a continuing pattern. The Beatles and their narrative provided a seminal example of how bands work, and seemed to be ploughing the furrow for others.

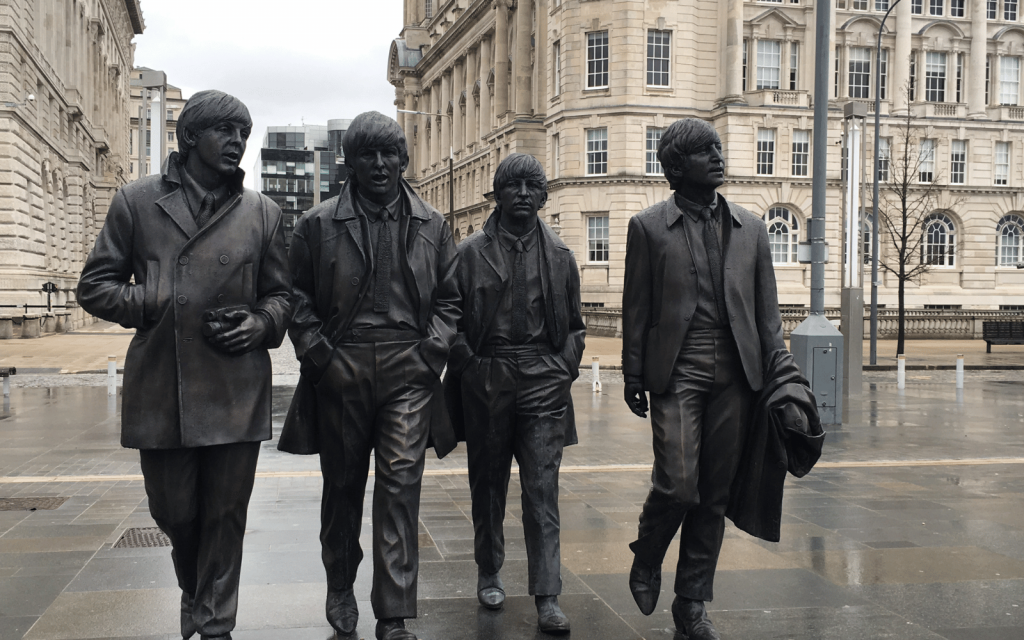

From their original formation as schoolboys (Ringo joined in 1962 when they started recording), to their enormous financial success and cultural impact, the Beatles laid down templates that others have followed. Lennon and McCartney’s first meeting at a church fete in 1957 is now the stuff of legend.

Their innovations in the studio, assisted by producer George Martin, helped to make recordings – especially albums – a central feature of the popular music experience. They emerged into professional practice together, splitting as they formed new relationships and moved onto the next phases of their life while still relatively young men.

Bands are simultaneously social groupings, creative units and economic entities. The economic “brand” can obviously run on for many years after the others have stopped. There is also long history of posthumous releases, including Jimi Hendrix, Elliott Smith and Prince, even Otis Redding’s defining hit (Sittin’ On) The Dock of the Bay. Demo recordings, unheard live performances and radio broadcasts are all established parts of artists’ catalogues.

This becomes complicated, though, when the act in question is a collective with deceased members whose presence on the recording is technologically facilitated. A key example is the Beatles 1995 Anthology project, which saw the surviving members revisit John Lennon demos from a cassette given to McCartney by Yoko Ono, and add new parts to finish the songs.

This wasn’t entirely unique. Queen’s Made In Heaven, in the same year, saw the band finish songs that Freddie Mercury worked on in the studio before he died. But it did involve resurrecting fragments of home recordings to clean them up for the commercial market.

The technology wasn’t sufficient at the time to properly isolate Lennon’s voice on Now and Then, so it was abandoned until Peter Jackson used machine learning to remove noise from source recordings for Get Back. By this time George Harrison had died, so this technology allowed McCartney and Starr to return to the song, incorporating Harrison’s guitar solo from the aborted 1990s attempt.

Come together

We can, then, consider the process behind this latest song in evolutionary rather than revolutionary terms. The possibilities of multi-track recording since the 1950s mean it’s long been the case that musicians have worked separately on the same song. As George Harrison said of The White Album:

There was a lot more individual stuff … people were accepting that it was individual. I remember having three studios operating at the same time. Paul was doing some overdubs in one, John was in another and I was recording some horns or something in a third.

Even when the Beatles were together, many canonical songs were the work of only one or two of them. McCartney wrote Yesterday and Blackbird alone, and is the only Beatle who plays on them. The Ballad of John and Yoko didn’t feature Harrison or Starr.

And the former band members played on each other’s “solo” records too. There are more Beatles on Harrison’s All Those Years Ago, or Lennon’s Instant Karma than on some of the band’s tracks. They all played separately on Starr’s 1973 album Ringo.

Read More: Virtual influencers: meet the AI-generated figures posing as your new online friends – as they try to sell you stuff

So Now and Then continues longstanding practices, going back to their heyday. Its status as the final Beatles song, though, reveals technological limitations. AI can create convincing facsimiles, but can’t replicate the facts of who actually played or sang the various parts, which is a central plank of what constitutes a band.

Audiences ascribe authenticity to music in many ways, and core among these for bands is the line-up – some acts have effectively replaced key members within the brand, others have had less success. It’s often a source of debate, at least, with “classic” line-ups being those that earn the audience stamp of authenticity.

So what of the song itself? It won’t supplant the likes of Hey Jude or Help in The Beatles’ musical pantheon. That bar, though, is high and the plangent piano-led ballad has a familiar yet distinctive arrangement, steeped in nostalagia but affecting on its own terms nevertheless. Lennon’s voice is clearer than on previous reconstructions and the harmonies sound like, well … The Beatles.

In that sense, what’s at the heart of this project is the presence – even spectrally – of the actual four people who made up the creative and social underpinning for the brand. The “last” Beatles song sees them demonstrating the importance, even as a coda to their recording career, of the interpersonal connections that set things in motion in the first place.

- is a Senior Lecturer in Popular and Contemporary Music, Newcastle University

- This article first appeared on The Conversation