Generative AI tools such as Midjourney, Stable Diffusion and DALL-E 2 have astounded us with their ability to produce remarkable images in a matter of seconds.

Despite their achievements, however, there remains a puzzling disparity between what AI image generators can produce and what we can. For instance, these tools often won’t deliver satisfactory results for seemingly simple tasks such as counting objects and producing accurate text.

If generative AI has reached such unprecedented heights in creative expression, why does it struggle with tasks even a primary school student could complete?

Exploring the underlying reasons helps sheds light on the complex numerical nature of AI, and the nuance of its capabilities.

AI’s limitations with writing

Humans can easily recognise text symbols (such as letters, numbers and characters) written in various different fonts and handwriting. We can also produce text in different contexts, and understand how context can change meaning.

Current AI image generators lack this inherent understanding. They have no true comprehension of what any text symbols mean. These generators are built on artificial neural networks trained on massive amounts of image data, from which they “learn” associations and make predictions.

Combinations of shapes in the training images are associated with various entities. For example, two inward-facing lines that meet might represent the tip of a pencil, or the roof of a house.

But when it comes to text and quantities, the associations must be incredibly accurate, since even minor imperfections are noticeable. Our brains can overlook slight deviations in a pencil’s tip, or a roof – but not as much when it comes to how a word is written, or the number of fingers on a hand.

Read More: Chatbots can be used to create manipulative content — understanding how this works can help address it

As far as text-to-image models are concerned, text symbols are just combinations of lines and shapes. Since text comes in so many different styles – and since letters and numbers are used in seemingly endless arrangements – the model often won’t learn how to effectively reproduce text.

The main reason for this is insufficient training data. AI image generators require much more training data to accurately represent text and quantities than they do for other tasks.

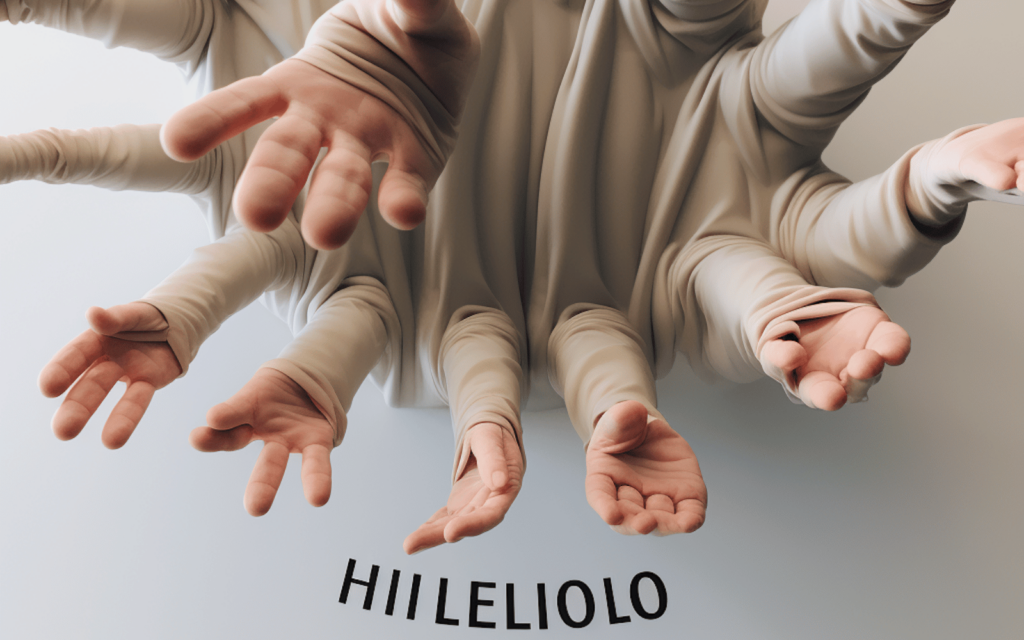

The tragedy of AI hands

Issues also arise when dealing with smaller objects that require intricate details, such as hands.

In training images, hands are often small, holding objects, or partially obscured by other elements. It becomes challenging for AI to associate the term “hand” with the exact representation of a human hand with five fingers.

Consequently, AI-generated hands often look misshapen, have additional or fewer fingers, or have hands partially covered by objects such as sleeves or purses.

We see a similar issue when it comes to quantities. AI models lack a clear understanding of quantities, such as the abstract concept of “four”.

As such, an image generator may respond to a prompt for “four apples” by drawing on learning from myriad images featuring many quantities of apples – and return an output with the incorrect amount.

In other words, the huge diversity of associations within the training data impacts the accuracy of quantities in outputs.

Will AI ever be able to write and count?

It’s important to remember text-to-image and text-to-video conversion is a relatively new concept in AI. Current generative platforms are “low-resolution” versions of what we can expect in the future.

With advancements being made in training processes and AI technology, future AI image generators will likely be much more capable of producing accurate visualisations.

It’s also worth noting most publicly accessible AI platforms don’t offer the highest level of capability. Generating accurate text and quantities demands highly optimised and tailored networks, so paid subscriptions to more advanced platforms will likely deliver better results.

- is a Professor, Director of Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research and Optimisation, Torrens University Australia

- This article first appeared on The Conversation