Humans are naturally afraid of the dark. We sometimes imagine monsters under the bed and walk faster down unlit streets at night. To conquer our fears, we may leave a night light on to scare away the monsters and a light over the porch to deter break-ins.

Yet, in huddling for safety under our pools of light, we have lost our connection to the night sky. Star counts by public awareness campaign Globe at Night revealed that, between 2011 and 2022, the world’s night sky more than doubled in artificial brightness. Yet local interventions can create meaningful change.

Light pollution is cutting us off from one of nature’s greatest wonders, harming wildlife and blocking research that could help fight climate change. Stars are more than pretty glimmers in the night sky. They have shaped the mythology of every human civilisation. They guide birds on their astonishing migratory journeys. And now we need to do our bit to prevent light pollution so stars can be part of our future.

The human eye can detect around 5,000 stars in the night sky. But the light emitted by skyscrapers, street lamps, and houses obscures all but a handful of the brightest stars.

Our ancestors used the rising and setting of the constellations as calendars. They also navigated by the stars as they searched for new lands or traced nautical trade routes. Sailors don’t normally use the stars to navigate any more, but they are still taught how to, in case their navigation systems break down.

Migratory animals, including birds and insects, are drawn away from their natural flight paths by the beckoning “sky glow” of cities. In the summer of 2019, Las Vegas was invaded by millions of migrating grasshoppers, while the beams of New York’s 9/11 Tribute in Light are a magnet for flocks of migrating songbirds flying at night.

Disoriented by the bright city lights, birds crash into towering skyscrapers. Insect numbers are collapsing worldwide and light pollution is making matters worse by disrupting their nocturnal life cycles.

What is light pollution

Light pollution is caused by the same physics that turns the sky blue during the day. Sunlight is made up of all the colours of the rainbow and each colour has a different wavelength. The air that surrounds us is composed of tiny particles (such as oxygen and carbon dioxide molecules).

As light from the Sun makes its way through the air, it is scattered by these particles in random directions. Blue light (with shorter wavelengths) is scattered more than red light (which has longer wavelengths). As a result, our eyes receive more blue light from every direction in the sky.

At night, light scattered by the same air particles causes the sky to shine down on us. A small fraction of this sky glow is caused by natural sources, such as starlight and the Earth’s atmosphere. But most of the light that creates sky glow is artificial.

Light pollution also affects our ability to study the universe. Even modern observatories, built on remote mountaintops, are affected by the encroaching sky glow from growing, sprawling cities. Light pollution is so widespread that three quarters of all observatories are affected.

Looking up

There is no reason to despair, though. We created light pollution; we can fix it.

Around the world, dark sky associations are working to educate the public about the hazards of light pollution, to lobby for legislation to protect dark sky reserves and encourage people to reignite their connection with dark, star-studded skies.

Fighting light pollution begins at home. If you need to keep outside lights on for security, use shielded lamps that only shine downwards. Use light bulbs that do not emit violet and blue light as this is harmful to wildlife. Smart lighting controls will also help reduce your house’s effect on wildlife and make it easier for you to observe the night sky.

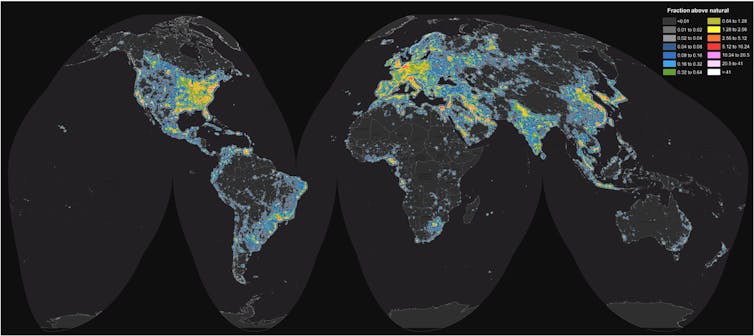

You will also find interactive maps that show how polluted the skies are in your area. These maps are created from data gathered by satellites and by citizen scientists taking part in annual star counts. You can help darken our skies, too.

In the UK, the 2023 annual star count will take place on February 17-24. And, wherever you are in the world, you can always take part in the year-long Globe at Night star count whenever you want.

The task is simple: step outside on a clear night, count how many stars you can see in a well-known constellation, such as Orion, and report back.

To defeat light pollution, we need to know how severe it is and what difference national policies and local interventions (such as replacing the street lights in your town) make. In the UK, for example, star counts show light pollution may have peaked in 2020 and has started to decline.

Perhaps the most important aspect of star counts is that they shine a light on our vanishing night skies and galvanize us to take action. Ultimately, it’s up to each and every one of us to reduce our effect on the sky, by changing the way we light our homes and neighbourhoods and by lobbying our representatives to pass dark sky legislation.

- is a Reader in Astrophysics, University of Portsmouth

- This article first appeared on The Conversation