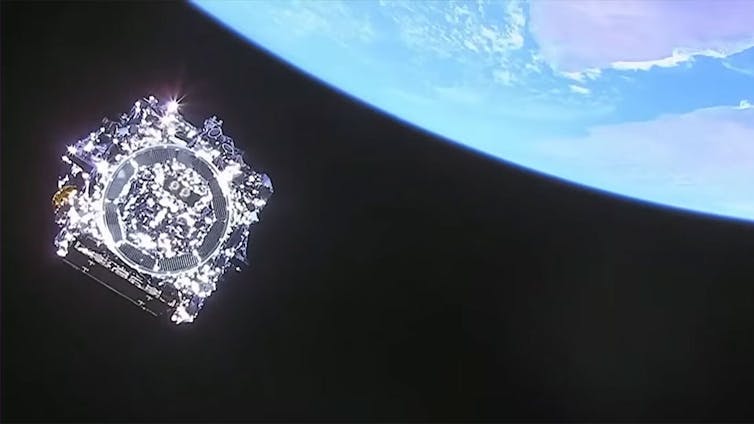

Since its launch on Christmas day, astronomers have eagerly followed the complex deployment and unfurling of NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope – the largest to ever take to the skies.

Right around the time this article is published, it’s expected Webb will have reached a place called the Earth-Sun “second Lagrange point”, or “L2”. This is a point in space about 1.5 million kilometres away from Earth (in the opposite direction from the Sun) where the gravity from both the Sun and Earth help to keep an orbiting satellite balanced in motion.

Now the astronomical community – including my team of Swinburne University astronomers – is preparing for a new epoch of major discoveries.

30 years and US$10 billion

In 2012, I wrote an article for The Conversation looking forward to the launch of Webb, and reminiscing about the amazing early days of its predecessor, the Hubble Space Telescope.

Read more: Hubble, Webb and the search for First Light galaxies

Back then, Webb’s planned launch date was in 2018. And when the project was originally conceived in the 1990s, the goal was to launch before 2010. Why did it take nearly 30 years, and more than US$10 billion (roughly A$14 billion), to get Webb off the ground?

First, it’s the largest telescope ever put into space, with a gold-coated mirror 6.5m in diameter (compared with Hubble’s 2.4m mirror). With size comes complexity, as the entire structure needed to be folded to fit inside the nose cone of an Ariane rocket.

Second, there were two major engineering marvels to accomplish with Webb. For a large telescope to produce the sharpest images possible, the mirror’s surface needs to be aligned along a curve with extreme precision. For Webb this means unfolding and positioning the 18 hexagonal segments of the primary mirror, plus a secondary mirror, to a precision of 25 billionths of a metre.

Also, Webb will be observing infrared light, so it must be kept incredibly cold (roughly -233℃) to maximise its sensitivity. This means it must be kept far away from Earth, which is a source of heat and light. It must also be completely protected from the Sun – achieved by a 20m multilayered reflective sunshield.

All of Webb’s major spacecraft deployments, including the unfurling of the primary mirror and sunshield, were completed on January 8. The entire process involved more than 300 single points of failure (mechanisms that had only once chance to work). The remaining tiny motions will take place over the next few months.

The main mission

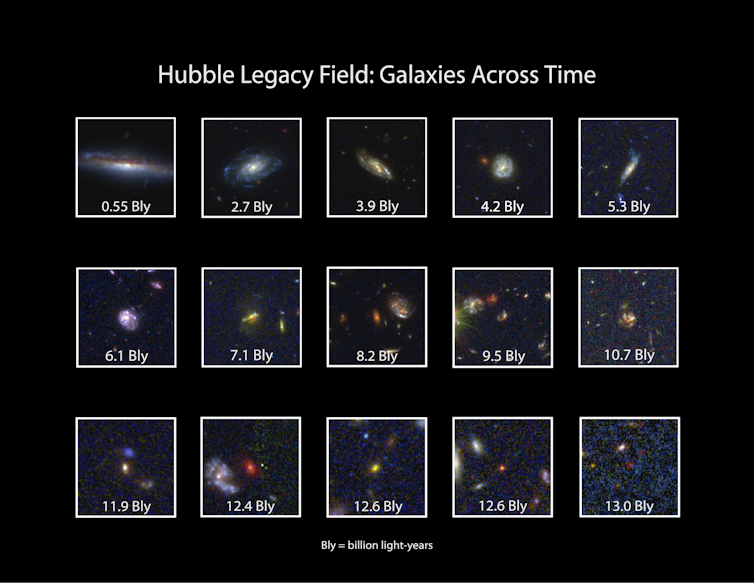

Webb’s primary mission will be to witness the birth of the first stars and galaxies in the early Universe. As the light from these very faint galaxies travels across the vast gulf of space, and 13.8 billion years of time, it gets stretched by the overall expansion of the Universe in a process we call “cosmological redshift”.

This stretching means what started out as extremely energetic ultraviolet radiation from young, hot and massive stars will be received by Webb as infrared light. This is why its mirrors are coated in gold: compared with silver or aluminium, gold is a better reflector of infrared light and red light.

Webb will see much farther into the infrared than Hubble could. It’s also up to a million times more sensitive than ground-based telescopes, where the light from distant galaxies is drowned out by the infrared emission of Earth’s own hot atmosphere.

Because of these previous technological limitations, the first billion years of cosmic history has barely been explored. We don’t know when or how the first stars formed. This is a complex question as stars produce heavy elements when they die. These elements pollute the interstellar gas in galaxies and change how this gas behaves and collapses to form later generations of stars.

All current star formation we can observe, such as in the Milky Way, is from enriched interstellar gas. We haven’t yet seen how stars form in pristine gas, which is without any heavy elements – as such a state hasn’t existed for more than 13 billion years.

But we think formation from pristine gas likely had a large effect on the properties of the first stellar populations.

A deep space observatory

In addition to studying the early Universe, Webb will be a NASA “Great Observatory” and will support a diversity of other projects.

It will allow scientists to peer into regions obscured by dust, such as the centres of galaxies where supermassive black holes lurk, or regions of intense star formation in our galaxy and others. Webb will also be sensitive to the coldest objects, including very low mass stars, and planets orbiting other stars within the Milky Way.

One big improvement on Hubble is that Webb will be well-equipped for spectroscopy, dissecting light into its component wavelengths. This will let us measure the cosmic redshift of galaxies precisely, and figure out what elements they’re made of.

Closer to home, Webb will help us find molecules such as water, ammonia, carbon dioxide (and many others) within the solar system, the Milky Way and nearby galaxies. It will be able to see these in the atmospheres of planets around nearby stars, which is particularly exciting for the search for extraterrestrial life.

Read more: The James Webb Space Telescope will map the atmosphere of exoplanets

Astronomers await with anticipation for the first data to be collected in the next few months. While the most dramatic and risky mechanical motions have been completed, the telescope continues to move, and the mirror segments are making tiny nanometre-sized motions to bring it into a focus. This will take many weeks as the telescope cools to its operating temperature.

For myself, perhaps the most exciting aspect to look forward to is the completely unknown. With Webb, we’ll be observing a previously murky cosmic era, when physical conditions were very different to those in the modern Universe.

The history of astronomy suggests we can expect paradigm-shifting discoveries.

- is a Director & Distinguished Professor, Centre for Astrophysics & Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology.

- This was first published in The Conversation.