As a social media platform, Twitter does not have the most glowing reputation. If you just rely on what you hear about it, you might think Twitter is no more than a hotbed for raging politics and viral campaign hashtags. But is that all there is?

The news media’s intense focus on political strife is misleading. In our new research, we studied Twitter from a different angle, and found it has important social functions as well.

This matters. As calls for social media regulation grow, it’s critical we see Twitter and other platforms in all their facets to make sure any possible new legislation affecting the social media platform doesn’t cause collateral damage in other areas.

In our study, we developed the term “phatic sharing” to describe Twitter activity that serves such a social function.

It’s remarkable that the phatic practices from the early days of the platform still persist after more than a decade, and it should give us hope that Twitter and other social media platforms may not be lost entirely to the political partisans and propagandists.

“The ties that bind” – Prime Minister Marape 🇵🇬 and Prime Minister Morrison @ScottMorrisonMP 🇦🇺 discover they’re wearing matching PNG ties #auspol @SBSNews pic.twitter.com/GafVUHn392

— Brett Mason (@BrettMasonNews) July 22, 2019

It’s a symptom of the biases in news coverage as well as in much scholarly research that such social practices on the platform are often overlooked, and that we focus instead mainly on high politics.

Twitter in a day

Rather than looking only for the hashtags and accounts we knew about already, our research took a snapshot of all Australian Twitter activity on an ordinary day in 2017, analysing 1.3 million tweets.

This helped us find user practices often overlooked by researchers and journalists, precisely because they don’t seek the limelight and don’t attach to visible hashtags and viral memes.

We found that hashtags like #auspol constitute a minority practice: more than three-quarters of all Australian tweets that day did not contain any hashtag. This means that any research that only focuses on hashtags like #auspol fails to capture the full range of Twitter activity.

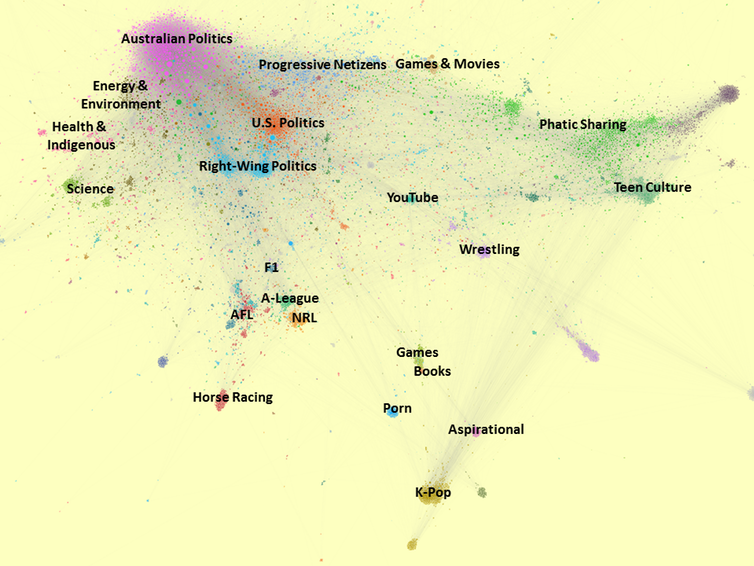

The breadth of topics over the course of the day becomes clearer from a network visualisation of interaction patterns among Twitter users, shown above.

Yes, there’s a solid cluster of users talking about domestic and international politics. But similarly, there are many other groups in the network that stay well away from such topics and talk about what’s important to their own lives.

Shooting the breeze

Of the distinct groups of accounts we identified through our network analysis, the most numerous and most active over a day are the phatic sharers – a cluster of accounts using Twitter in a completely different way from the political hashtag warriors.

There is no clear thematic focus to what these accounts do. Roughly half their tweets are retweets, contain URLs, or both, and a quarter are original tweets that neither @mention or retweet anyone else. Only about 5% of their tweets are hashtagged.

So, we interpret this group as using Twitter essentially as a place to hang out and shoot the breeze.

They’re not interested in a wider reach for their tweets (otherwise they’d use hashtags). They mainly share personal updates and observations, or they retweet the things they encounter as they hang out on Twitter.

In other words, they’re using Twitter as it was originally intended, not as what it has become in the years since the social media platform launched.

Not just ‘pointless babble’

Some might see such practices as a waste of time. A 2009 report on how people used Twitter at the time described similar activities as “pointless babble”.

But to dismiss what we see here so glibly would be a mistake. For the users involved, phatic sharing can be important for personal expression and as a tool to maintain social ties.

This means they’re posting updates, sharing links, and retweeting other people’s posts not because they contain breaking news or engage with national and international events, but because this continuous communicative presence on the platform has a social – phatic – function. This is similar to the small talk we might engage in at work, with friends, or at social events.

Just watched 'Kubo and the Two Strings' then 'Your Name' in a row, off to sob myself to sleep bye guys

— Ben Minarelli (@italianplastic) January 1, 2018

It doesn’t matter so much what’s said, but that it is said at all. In offline reality, speaking and interacting maintains our place in the social network, rather than becoming just a silent bystander.

The same, it seems, applies on Twitter. For phatic sharers, simply following the tweets of others is not enough.

And that is perhaps the central point here: as a practice, phatic sharing reclaims Twitter as a truly social network, rather than simply as a source of breaking news or a place for public debate between politicians, journalists, and activists.

So next time we’re offended by Donald Trump’s latest Twitter outbursts, or frustrated by the predictably partisan battles in domestic political tweeting, why not just unfollow those accounts and find some more interesting people to connect with?

You’ll need to look beyond the trending hashtags (and in fact, beyond hashtags altogether) to find them, though.

- is Professor, Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology

- is Data Scientist, Queensland University of Technology

- This article first appeared on The Conversation