On my bedside cabinet, next to my alarm clock, is a jar holding my cufflink collection. One set contains seven odd cufflinks. They are bold in colour, now a bit scratched with flaking paint, but with clear geometric designs: a squat Z, S and T, an L, a J, a square and lastly, the ever useful long bar.

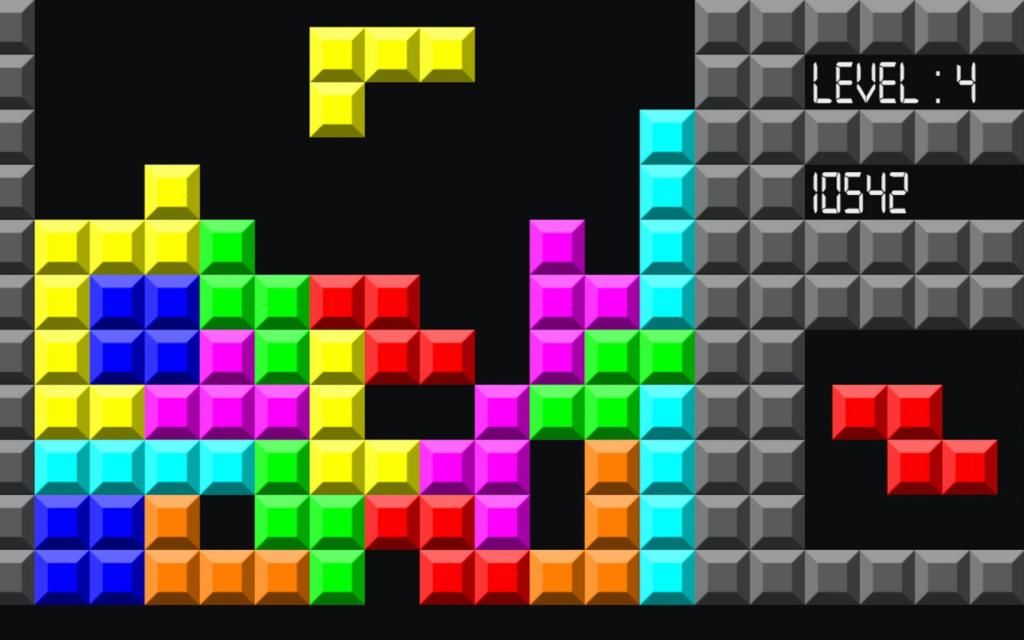

Even as a lecturer in games development, I don’t tend to wear my game affiliations that boldly but these cufflinks, the odd badge and my Minecraft waistcoat are exceptions. There are very few video game elements that I could describe so simply that even some non-gamers would recognise. But I am, of course, talking about the shapes, or the “tetrominoes”, from the nearly 40-year-old game of Tetris.

Alongside Pac-Man, Super Mario, and Sonic the Hedgehog, Tetris was one of the first video games to break into popular culture. How else can you explain the recent release of the Tetris movie, starring Taron Egerton? Bizarrely, this film is based on what you think would be the rather dry legal arguments of the intellectual property rights of the game.

But within games lore, the tale of how Tetris came to be is legendary.

Alexey Pajitnov, a speech recognition researcher at the Soviet Union’s Academy of Sciences, developed a range of puzzle games in the early 1980s, by “borrowing” spare time on his workplace’s Electronika 60 computer.

The machine had no graphical display and so the games were displayed using text but Tetris still hooked many of Pajitnov’s colleagues. Soon it was on most computers in various Soviet organisations.

Pajitnov wanted to share his game, but this being the late Soviet Union era, he had little idea of how game publishing worked and his employers weren’t pleased about the “wasted” time on their expensive computer. Plus Soviet copyright law gave the state control over the software.

However, Pajitnov negotiated the rights to the Academy via his supervisor, who sent the game to Hungarian game publisher Novotrade. That led to Tetris seeing limited success behind the iron curtain.

In Hungary, Robert Stein of Andromeda Software saw Tetris, liked it and approached Pajitnov about obtaining the rights. Pajitnov responded via fax that he was interested. Stein took that fax and without drawing up a contract, proceeded to sell the rights at the 1987 Las Vegas Consumer Electronics Show.

Tetris became a massive success, being ported to multiple platforms and winning multiple awards. But what then followed was a protracted legal battle which stretched across continents, involved several gaming companies and numerous iterations of Tetris itself. There were versions on the Amstrad, the BBC Micro and the Apple II to name but three.

Eventually, in the late 1980s, Nintendo showed an interest in wanting to obtain Tetris for their upcoming Game Boy console. Since then, it’s practically been ubiquitous.

Quite simply, Tetris is one of the most engaging computer games ever devised. Some have tried to pin psychological aspects to it. The slow ramping up of difficulty is not just due to the increasing speed but also because your failures stay to thwart you and victories are therefore fleeting.

Tetris of old

For those of us old enough to have grown up with the first generation of home computers such as the ZX Spectrum, Tetris is our “when I were a lad” type of game. I still remember the drama of the thumping and ominous beat of the music on the Commodore 64, forgoing the catchy Russian folk song of the original.

It was a time when you couldn’t rely on the Oscar winning performances of your voice actors, the ultra-realism of your graphics or a sumptuous orchestral soundtrack. It was beeps and limited colours of obvious pixels, so the gameplay had to grab you even more to get that “just one more go” kick.

Doom is often cited as being the game featured across all platforms but I’d argue that Tetris really holds that crown. Having first played it on my Commodore 64, I went on to play it on my Amiga, many iterations on PC, then the Xbox 360. It’s available on the current generation of consoles, on phones and there is even a virtual reality version. All with the same essential gameplay. You can’t really mess with near perfection.

Having grown up with 8-bit graphics, it’s fascinating to watch my students, born decades after Tetris, copying that retro style for their modern games design.

When Phil Fish designed his game Fez, a successor to Tetris as a video game puzzler, he wanted to depict the remains of an ancient civilisation, but a video game ancient civilisation.

Look closely at the stone ruins of this long-dead race. They are made from recognisable, odd-shaped blocks: a squat Z, S and T, an L, a J, a square and lastly the ever useful long bar.

- is a Senior Lecturer in Games Development, Cardiff Metropolitan University

- This article first appeared on The Conversation