When you think of space-age materials, the same product that allowed the Phoenicians to dominate maritime culture more than 6,000 years ago doesn’t come to mind. And yet that’s the main component of the LignoSat, a new CubeSat from the Kyoto University that has just launched toward orbit.

LignoSat’s name is based on lignum, the Latin name for ‘wood’. It’s a collaboration between Kyoto University and Sumitomo Forestry, a Japanese company focused on sustainable wood products. The point of the project isn’t just to promote what Sumitomo does, though it’s also that. It’s also to test just how effective wood is as a space-age material.

LignoSat has wood

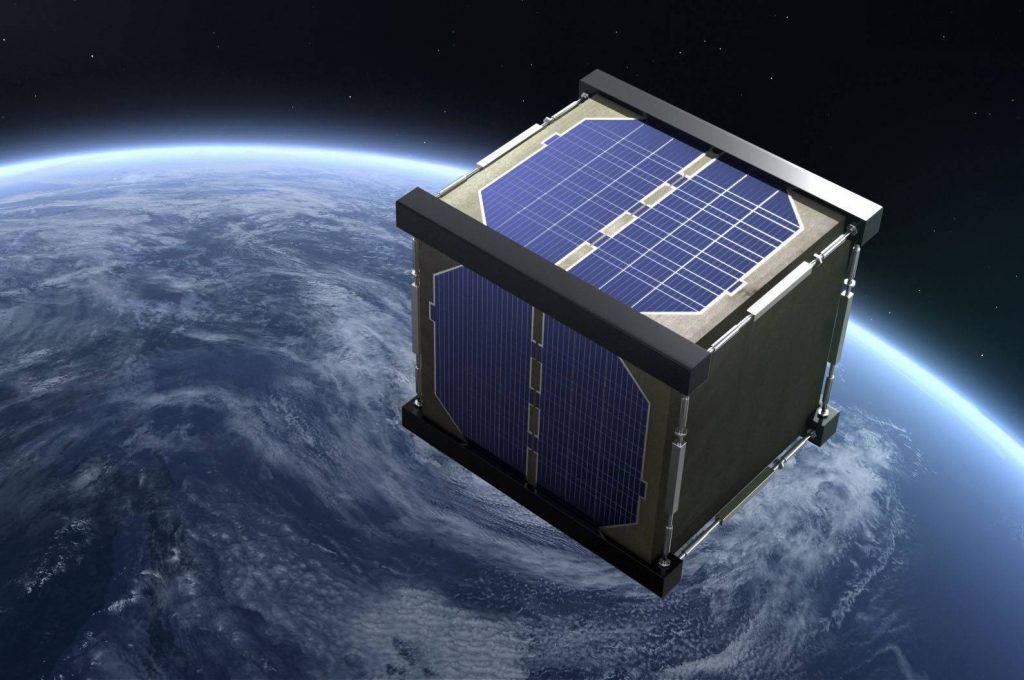

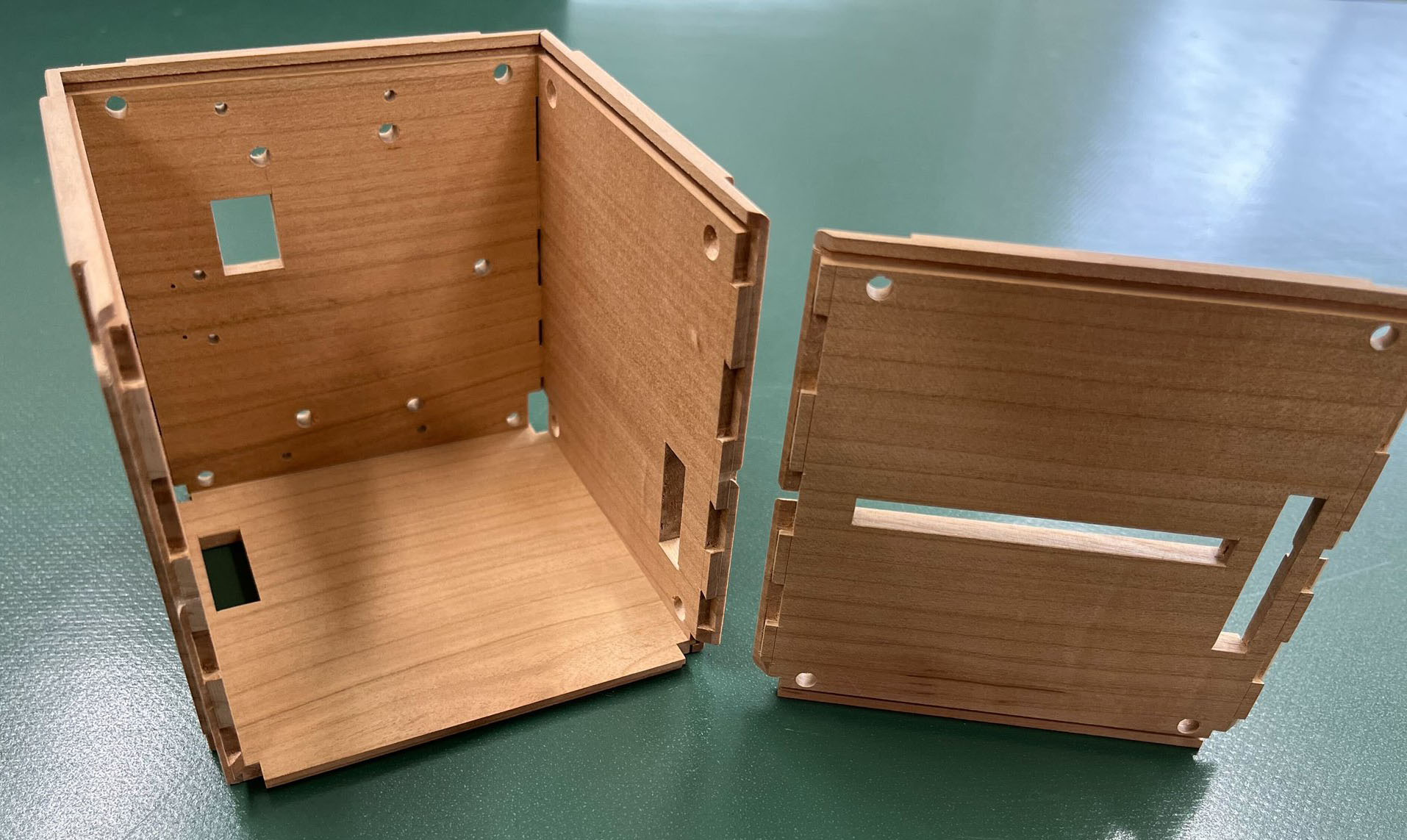

It’s safer — and cheaper — to make a wooden CubeSat and send it into orbit on a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch than it is to create a full-sized device and attempt to send it on a dedicated launch. The CubeSat consists of the scientific internals encased in an elegantly jointed wooden box, with solar panels mounted on the outside.

It’s safer — and cheaper — to make a wooden CubeSat and send it into orbit on a SpaceX Falcon 9 launch than it is to create a full-sized device and attempt to send it on a dedicated launch. The CubeSat consists of the scientific internals encased in an elegantly jointed wooden box, with solar panels mounted on the outside.

LignoSat has a few goals, the primary one being to find out whether satellites can survive being made out of wood — honoki, a Japanese variety, in this case. If they can, well… trees are a relatively cheap and renewable resource. These satellites can also be made lighter than their metal counterparts.

The other of LignoSat’s goals is to detect and communicate with amateur radio stations, replying to FM signals with a ‘thank you’ message on the UHF band. But a broader target is in sight for the Japanese project.

Read More: CubeSats, the tiniest of satellites, are changing the way we explore the solar system

Japan hopes, in the span of the next 50 years, to plant and harvest trees on terrestrial surfaces that aren’t Earth. The moon and Mars are fair targets and having trees in those places would solve at least some of humanity’s building materials problems. “With timber, a material we can produce by ourselves, we will be able to build houses, live and work in space forever,” said Japanese astronaut Takao Doi.

Using the material for satellites also means less waste and easier re-entry when decommissioned units are sent to a fiery death through Earth’s atmosphere. First, though, LignoSat must survive deployment and then its six-month stay in the cold vacuum of space.