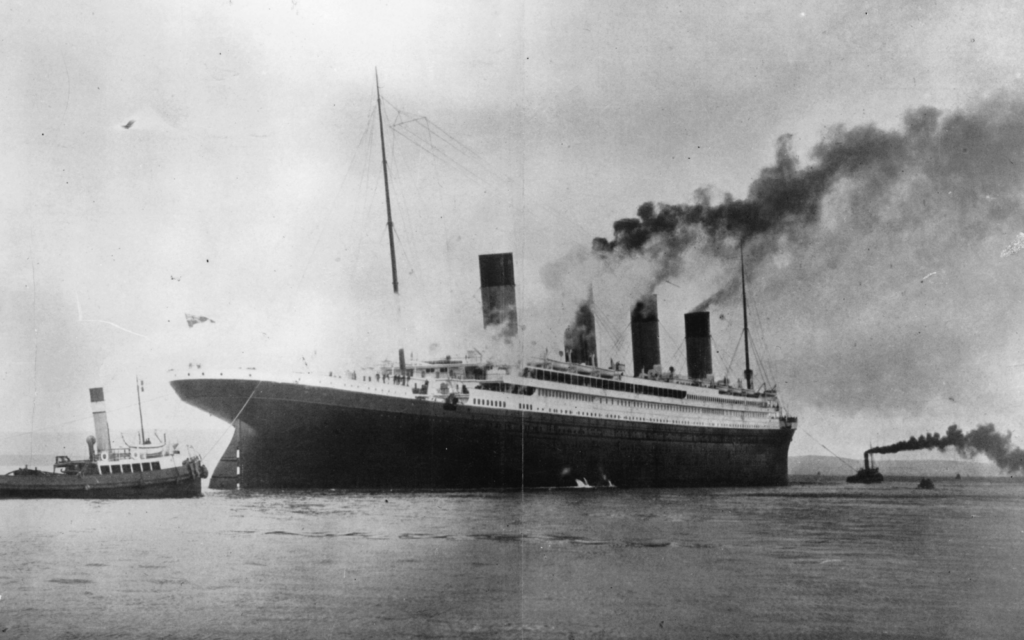

On TikTok, the world’s most famous shipping tragedy never happened. Or, to put it in the words of one conspiracy theorist: “The Titanic NEVER actually sank”.

During this half-minute video, the man who says this also peddles a favourite theory that the Titanic was actually replaced with its sister ship the Olympic, as part of an elaborate insurance scam.

Another TikTok video – that someone commented on “the titanic never sank!!!” – was seen 111 million times earlier this year before it was removed. Yet another conspiracy theory is that the sinking was a “hit job” by financier J.P. Morgan to eliminate opponents of the Federal Reserve, according to a fascinating long read on Titanic conspiracy theories on the short-form video service by the New York Times.

It’s easy to forget that conspiracy theorists have time to waste on such lesser-known irrationalities, but 11 million views prove how literally viral such misinformation can be.

While rational people tend to roll their eyes at people dumb enough to believe such drivel, the problem with such disinformation appearing on social platforms frequented by teenagers is deeply, deeply worrying.

A Titanic mistake

It’s where youngsters go for entertainment in this post-linear television age, saturated by streaming content, especially the short-form video that TikTok has become the biggest proponent of.

If you repeat a baseless fact often enough, it appears to become real – as former US President Donald Trump demonstrated with incorrect comments about Barack Obama’s birth certificate from Hawaii.

“Fundamentally, a 14-year-old is probably taught at school that the Earth is round and probably believes it, but with the frequency of watching videos over and over, they start questioning it,” Helen Lee Bouygues, who started Paris-based nonprofit Reboot Foundation to help fight misinformation, told the paper.

“The longer young adults were on TikTok, the more that they believe what they see,” she added.

TikTok differs from Twitter and Facebook, which have traditionally shown you content somehow related to who you follow. TikTok shows you what is trending and whatever you engage with.

“If someone is spending time on a video, it doesn’t matter if they really believe J.P. Morgan sank the Titanic, or if they believe, hey, this is a funny video, someone is talking about J.P. Morgan sinking the Titanic,” Megan Brown, a senior research engineer at New York University’s Center for Social Media and Politics, told the Times. “This is the same signal as far as TikTok is concerned, so they recommend more of that content.”

This is how truth gets eroded, she points out, while “people who believe in at least one conspiracy theory tend to believe in at least more than one”.

While the New York Times bemoans the decline in “proficiency in US history” in its education system, it’s arguably worse in South Africa, where our own teacher union-dominated schooling renders our children unable to read for meaning.

Where do young people – already alive in an age of streaming video on mobile phones as the default of entertainment – go when they can’t read?

Be afraid.

- This column was first published on Financial Mail.