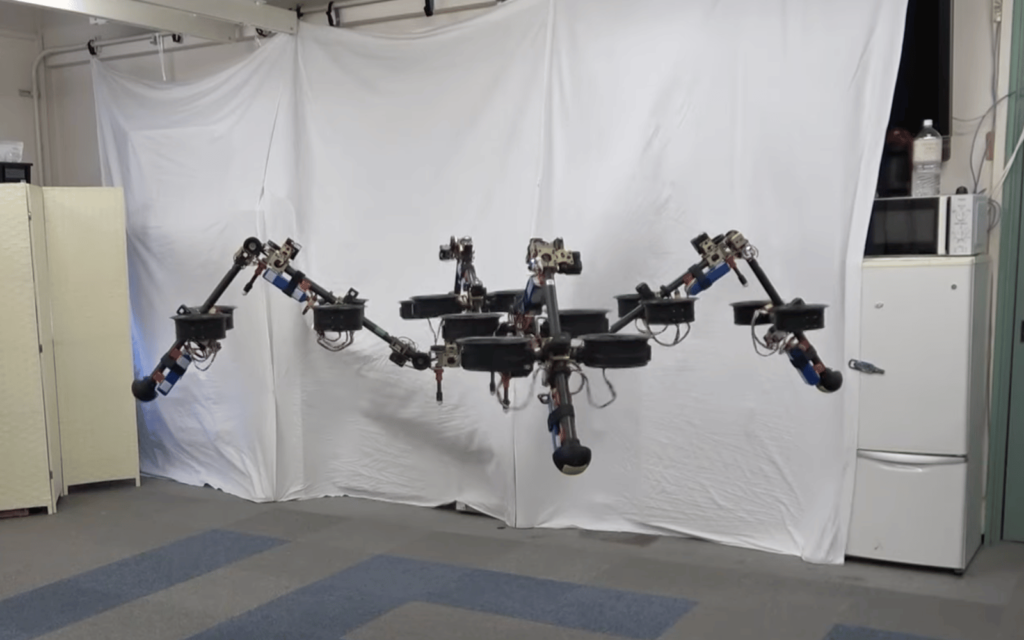

Robots are (mostly) brilliant. And they’re only going to get better. We’ve already gotten ones that can play the drums, tee off at the course and one that’s eyeing up humanity’s jobs (looking at you, Boston Dynamic’s Atlas). Then you get those whose only discernible purpose is to frighten the population. Meet SPIDAR – The University of Tokyo’s flying, crawling, terrifying robotic spider.

SPIDAR isn’t a typo, is supposed to be a clever acronym for ‘SPherIcally vectorable and Distributed rotors assisted Air-ground amphibious quadruped Robot’. Good luck saying that three times quickly. If you’ve partaken in our What Stuff is in the Box competitions, this naming convention should look rather familiar. But we won’t be giving one of these away anytime soon.

Spiders fly now? They fly now

On a normal day, getting any robotic thing off the ground is a pretty big ask. Just look at Boston Dynamic’s SPOT, it weighs around 30kg without any flight material attached. SPIDAR weighs roughly half that, coming in at 14kg – a design choice that helps the bot’s thrusters take off without needing any jet fuel first.

SPIDAR relies on 16 spherically vectorable dual thrusters to even move around at all. Despite the name, SPIDAR only has four legs, each with four thrusters attached. When needed, the thrusters can manoeuvre themselves to let SPIDAR rotate and get itself into a crawling position. Since the limbs are built using servomechanisms, or servos. Those aren’t able to hold the machine’s weight on their own so SPIDAR is constantly in a rhythmic bouncing motion to keep it upright.

Read More: San Francisco cancels its killer robot approval following protests

When it’s ready to fly, it positions all 16 thrusters downwards, giving it enough power to take off. Thankfully, for anything being chased by this monstrosity, it can only achieve a nine-minute flight time or eighteen minutes of walking before the battery needs a recharge. It’s a bonus that it’s quite loud and extremely slow, meaning it shouldn’t catch most people unawares. For now.

Obviously, SPIDAR is a long way off from being useful in any capacity. But it might prove useful for improving drone mechanics and soft landings. At least, that’s what SPIDAR is going for according to their paper on the subject. And don’t forget, there was once a time when Boston Dynamic’s first robot was capable of only basic movements. Give this thing ten years and an AI brain and we’ll probably wish we hadn’t.