If you recently bought a new bakkie, you might have found its manufacturer keeps telling you they can’t deliver it because of a global shortage of a key component.

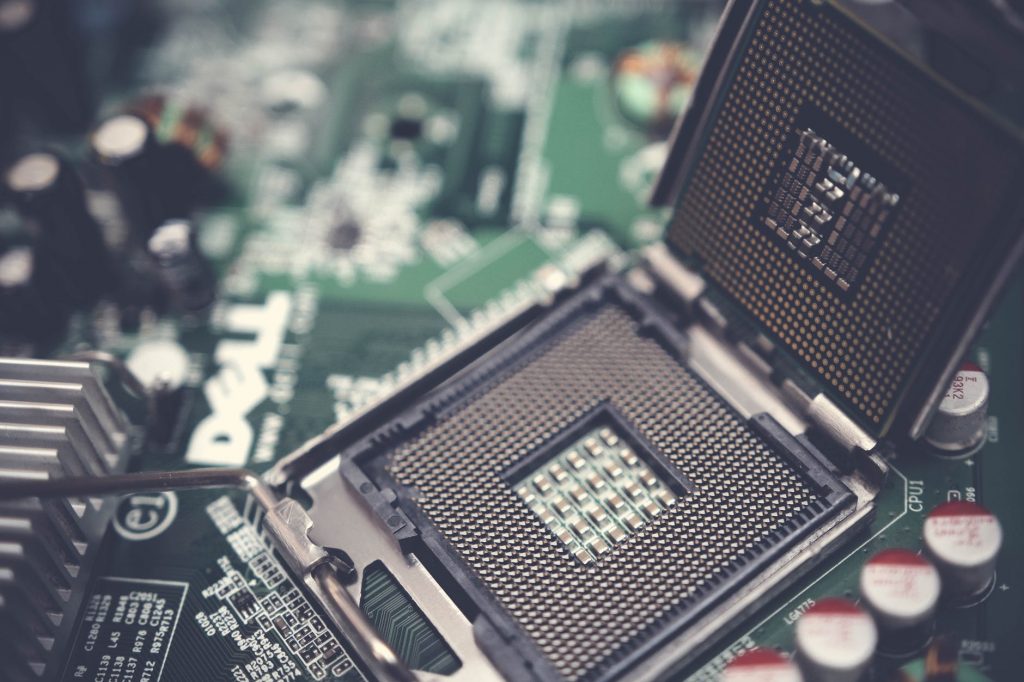

You’d be surprised to discover that crucial part is actually a microprocessor, not that different from the chips in your smartphone.

Technology has reached its tentacles into so much of our lives that the shortage caused by the pandemic has this strange knock-on effect in such vastly different industries as automation and telecoms.

Ardent gamers desperate for their new Xbox or PlayStation consoles are similarly affected – and arguably the most vociferous (and deeply hurt) of those deprived of their new goodies.

Last week it was the turn of Foxconn, the Taiwanese outsourced powerhouse which makes Apple’s mobile devices among others, that warned it would be affected by the global shortage.

Foxconn is forewarning that it expects a 10% decline in its products – read 10% less iPhones – and there is a significant knock-on effect for the rest of the industry.

The chip shortage forced Apple to delay its launch of the iPhone 12 last year by two months. Apple is the largest purchaser of semiconductors, on which is spends $58bn every year.

“Chips are everything,” said media and tech analyst Neil Campling from Mirabaud. “There is a perfect storm of supply and demand factors going on here. But basically, there is a new level of demand that can’t be kept up with, everyone is in crisis and it is getting worse.”

Apple’s arch-rival in the smartphone segment, Samsung, is also the biggest chip maker in the world – and Apple buys a huge portion of its components from the South Korean powerhouse.

“There’s a serious imbalance in supply and demand of chips in the IT sector globally,” Samsung’s co-chief executive Koh Dong-jin said.

The shortage was exacerbated by – of all things – fierce winter storms in Texas. Most people will be scratching their heads wondering, “Why Texas?”. The lone star state is home to an enormous tech industry. It’s capital Austin, where the annual South by South West (SXSW) usually happened before Covid, is also the home to Dell computers and SolarWinds, which was at the heart of a major hack of US agencies.

Texas also has a huge chipmaking industry, including a facility owned by Samsung, which was rumoured in January to be considering a $10bn fabrication plant in Austin. The winter storms, which caused rolling blackouts, therefore hit the Texas semiconductor industry as hard as loading shedding by Eskom does to the whole of South Africa.

Part of the shortage problem is also related to former #Presidunce Donald Trump’s trade war with China. Aware that a ban on American products was in the offing, Huawei bought up all the chips and other crucial components it could. As I warned at the time, Trump’s executive orders about Chinese firms accessing American technology is going to ultimately backfire against the US because it has hastened China 2025, the emerging superpower’s own plan to build its own high-tech industry.

It has certainly already had a serious impact because Huawei – quite rightly trying to prevent external forces, whatever they are – from impact its business process. The new US administration, with so many Trump-caused scandals and diplomacy fires to put out, hasn’t said what it will do with these sanctions.

In the meantime, there aren’t enough chips for new phones, new Xboxes and new cars – demonstrating, yet again, the importance of the global supply chain for the functioning of the world’s economies.

This article first appeared in the Daily Maverick.