Before Monday most South Africans would probably never have heard of competition commissioner Tembinkosi Bonakele. But after his scathing attack on the “concentration and duopoly” of Vodacom and MTN as “a bias against the poor” they’ll know who he is.

He gave the two biggest networks two months to cut their prices by a third to half

“failing which we will consider prosecution for excessive pricing”.

This “highly concentrated” situation, where the duopoly account for about 70% of South Africa’s mobile market share, is finally coming to a head. Consumers will be relieved that there is movement and significant movement at that.

MTN and Vodacom lost a combined R22bn on Monday when Bonakele made his announcement that data prices are “excessive,” flanked by ministers minister of trade and industry Ebrahim Patel and communications minister Stella Ndabeni-Abrahams.

The interesting thing about this week’s bombshell announcement is that it’s from the competition watchdog, and not the regulator Icasa. The years-long data services market inquiry, a draft of which was published in April, found that both MTN and Vodacom charge significantly less in other countries they operate in Africa.

Both operators have pointed out they are still without the spectrum that the government should have licenced years ago to enable for cheaper and better wireless signals. MTN says it has spent over R50bn in the last five years to build a 4G network without the actual spectrum itself.

Vodacom says it has lowered the effective price of data by ̄about 50% since March 2016, while pointing out discrepancies between this week’s competition ruling and previous Icasa findings.

But they both really don’t have much room to manoeuvre. An attempt to sue the competition watchdog would have as negative public outcry as their heavy-handed and ham-fisted response to the rollover of data regulations that Icasa imposed earlier this year.

This is a competition issue, not a regulatory one and the consolidation of power means the MTN-Vodacom duopoly have been immune to many forces that should have brought prices down. The introduction of smaller operators (Cell C, Virgin Mobile and even Telkom) which have tried to bring about a price war simply hasn’t translated into cheaper prices from the top two networks.

MTN SA makes a third of its revenue from data, or R12.9bn; while Vodacom’s earns 43%, or R24bn, so there is a lot at stake for them.

Patel said the findings showed “profitability levels are very high, reflecting anti-competitive outcomes” and that “data costs are critical to the performance, not just of the digital economy, but to the entire economy”.

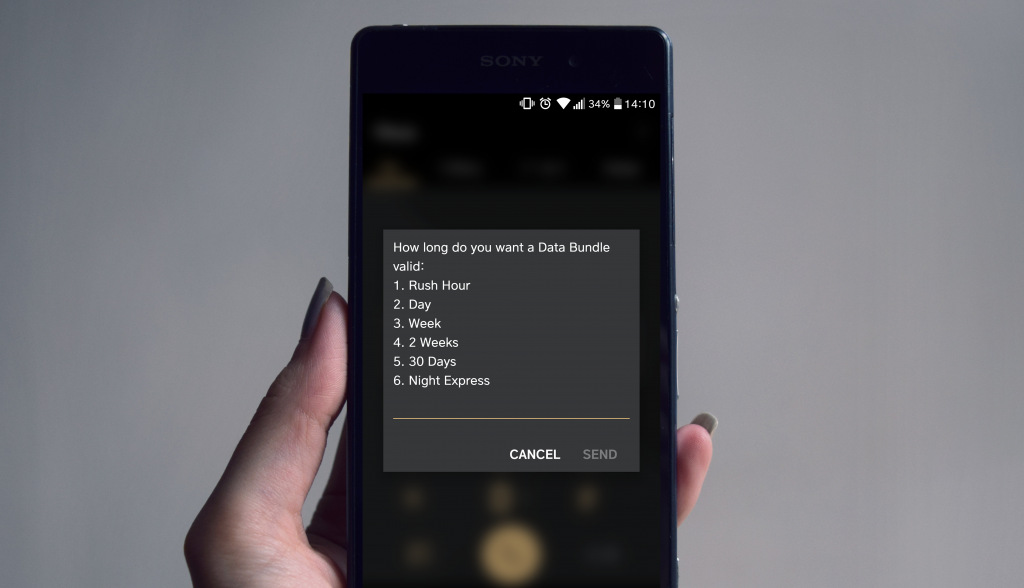

Icasa found earlier this year that the data bundles were more expensive for poorer customers, which Bonakele echoed this week.

A sobering statistic is that between 25% and 33% of smartphone users cannot afford data, according to researchers World Wide Worx.

When even finance minister Tito Mboweni shouts out “#DataPricesMustFall” during his budget speech in February, then something has to change.

This week’s blistering assessment by the competition watchdog is what many consumers would have been wishing for, not only as a way to decrease their telecoms costs but to be able to experience the internet without fear of running out of airtime.

This column first appeared in Financial Mail