My favourite thing that the great photographer David Goldblatt said was in answer to why he didn’t shoot colour film during the dark days of racial repression: “During those years colour seemed too sweet a medium to express the anger, disgust and fear that apartheid inspired.”

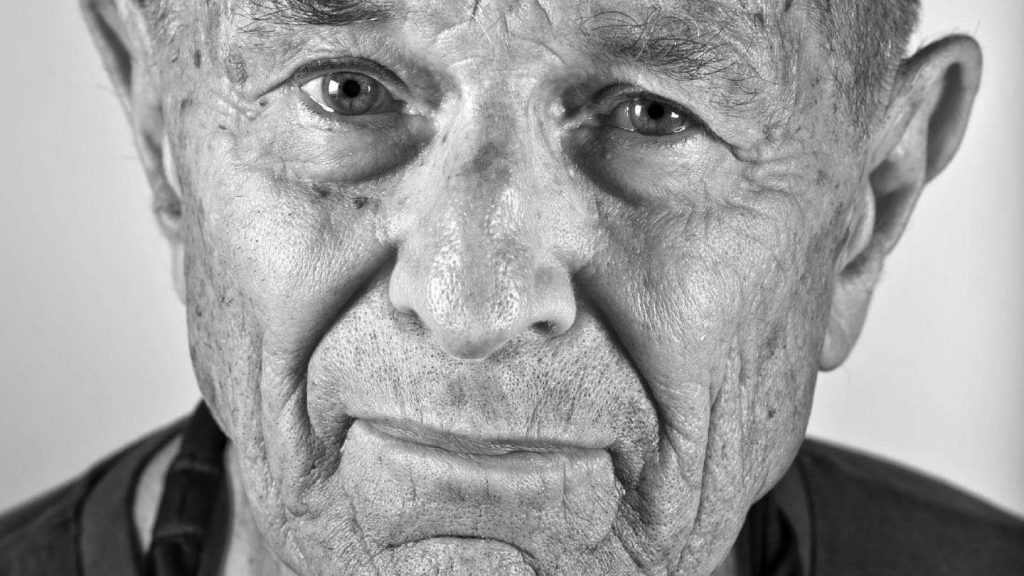

Last Monday, news broke that this great documenter of South Africa’s dark legacy had passed away. He was 87.

Earlier in May Sam Nzima, the man who gave the world the iconic image of young Hector Pieterson being carried during the 1976 student uprising, died at the age of 83.

They were both part of a generation that depicted the horrors of apartheid in all its tragedy; and sometimes, through Goldblatt’s lens, tragi-comedy. It was the golden age of photojournalism, in part because photography was so difficult. Taking a picture required a skillset that took years of practise, expensive equipment, an ability to gauge the quality of light, set the exposure and the speed of the film, and know how to frame a picture. Press photographers often had to do this under extreme pressure, as Mzima did that fateful day in 1976.

The Bang Bang Club of Kevin Carter, Greg Marinovich, Ken Oosterbroek, and João Silva would become the most famous photography cowboys of the chaotic early 1990s.

Marinovich and Carter won Pulitzer Prizes for their haunting images, Greg for a horrific necklacing and Kevin for THAT image of a starving Sudanese child being stalked by a vulture. Silva continued taking pictures after he stood on a landmine in Afghanistan in 2010 and still works for The New York Times.

The Bang Bang Club were the photographers all of us young journalists looked up to, and aspired to be. I was lucky enough to work with Marinovich when he was the picture editor at the Mail & Guardian and I was a young reporter. He always had time for us youngsters, sharing tips, telling war stories, being a mentor.

I was also lucky enough to know Goldblatt, through his son Rasada, who is still a good friend. His images of South Africa are among the greatest, especially his moving images of migrant workers and forgotten communities living in poverty.

Steadfastly using black and white photography for most of his career, Goldblatt captured the history of our country across the decades with haunting images.

When I was a teenager I discovered journalism and photography through a man who would be my mentor for decades, the great photojournalist John Brett Cohen. Being a photographer seemed a noble pursuit in those dark years of the 1980s and Cohen’s influence on my life was one of the reasons I became a journalist, experimenting with taking my own pictures. Given how complex film photography was, I was told as a young reporter to choose. Because writing was what I had always done, I chose that.

Imagine telling a young reporter today they would have the luxury of only doing one form of what would be called “content capturing” now. They are expected to take notes, pictures, tweet, post images and video to Twitter, Instagram and Facebook Live and then write a story.

But times have changed the underlying technology. Until about 15 years ago, when digital photography really took off, and the preceding 10 years when compact cameras became mainstream, it wasn’t easy to take a good picture. Now, we all have smartphones and capture everything with comparative ease.

It makes the haunting, epoch-capturing images taken by Goldblatt, Mzima, Marinovich and the Bang Bang Club all the more moving.

This column first appeared in Financial Mail