If 2021 was the year of the Great Resignation, then 2022 is likely to be the year of the Great Breakup.

After many years of slow build-up, the US government – both lawmakers and various attorneys-general, as well as the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – has got a head of steam and is taking on the Big Tech firms.

It won’t conclude this year – big corporates have big budgets for big lawyers – but this is the beginning of the beginning.

In November the FTC refiled its case against Facebook, now called Meta Platforms, where it is alleging that the social giant “interfered with the competitive process by targeting nascent threats through exclusionary conduct”.

New FTC chair Lina Khan is a seasoned anti-monopolist activist for consumers. Meta had the distasteful chutzpah to ask her to recuse herself as if her prior activism – and academic excellence – wasn’t the reason she got the job.

Facebook had recognized that the “transition to mobile posed an existential challenge” and it only had “a brief window of time to stymie emerging mobile threats,” says the FTC’s new filing of its lawsuit, which was initially dismissed by the judge who asked for more specific information.

“Failing to compete on business talent, Facebook developed a plan to maintain its dominant position by acquiring companies that could emerge as, or aid, competitive threats. By buying up these companies, Facebook eliminated the possibility that rivals might harness the power of the mobile Internet to challenge Facebook’s dominance.”

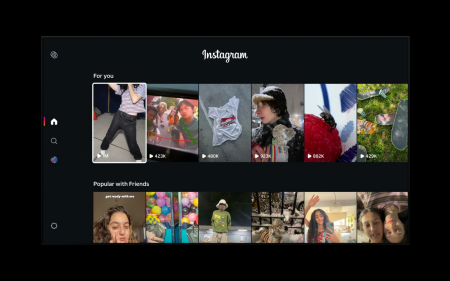

That is the very definition of anticompetitive behaviour, using your market dominance to prevent competition. Instead of innovating itself, Facebook bought Instagram for a then eye-watering $1bn in 2012 and then spent an even more eye-watering $19bn on WhatsApp in 2014.

If you can’t beat ’em, buy ’em

The social giant knew its young users were leaving Facebook Blue — as it is called internally — because they didn’t want to hang around on the same social network as their parents and grandparents. The cool kids were on Instagram, evolving from text updates to photographs, as social media itself evolved. So Facebook acquired it.

Then, when it realised WhatsApp was an infinitely more popular messaging app than its own clunky Messenger, it snapped up that competitor.

That is pretty anti-competitive, or antirust as the US calls it.

When Facebook started integrating the back-end software for all three disparate messaging apps a few years ago, it was met with increasing revolute – including last year’s now-infamous demand that users on WhatsApp agree to the terms for Facebook’s existing e-commerce customers so that they could directly market to WhatsApp users.

The way Facebook abused this dominance, the FTC claim, is how it pressurised developers into using its application programming interface (API) at the cost of being able to work with other competitors.

Facebook therefore “retooled its API policies into an anticompetitive weapon,” the FTC argues. It wants Meta to sell both of these apps.

WhatsApp now has over 2bn users, while Instagram and Messenger each have over 1bn. Facebook, with 2.8bn monthly active users itself, therefore controls the social media and messaging apps for half of the 7bn people on the planet.

This is the year of slow retribution. Beginning with an antitrust court case, and perhaps ending with criminal charges against social media executives – it’s been a long time coming. Let’s hope it was worth the wait.

- This article first appeared in the Financial Mail